Remote Consultations in Mental Health: Learning from Evaluation Report

September 28, 2021

Introduction

COVID-19 turbo-charged the use of remote consultations in mental health, with many services having to switch to video or telephone appointments almost overnight. But what has this meant for service users and staff, and what lessons can we take for the future?

This report, published jointly with south London mental health providers, local system partners, academics and service users examines the evidence on the impact of the shift to remote consultations, shares learning and provides recommendations for future practice. This work is ongoing so please check back to the Remote consultations in Mental health resource page for updates and the latest published papers.

Executive Summary

Remote Consultations in Mental health – Learning from Evaluation Executive Summary

COVID-19 has meant significant changes in how mental health services have been delivered. Appointments that would normally have taken place face-to-face have had to be moved to video or telephone consultations.

These changes are likely to have had an impact on all the people involved in mental health care – from service users to clinicians and other mental health professionals. There may have been positive and negative effects, or unexpected consequences. Currently, however, there has been no comprehensive evaluation of these effects.

This project is led by the three south London NHS Mental Health Trusts, working in conjunction with service users and academia to develop the evidence base in this area and form a learning healthcare system.

Through conducting a robust evaluation of the current evidence and identifying any potential gaps, the project aims to guide ongoing research, disseminate best practice, and inform the delivery of services now and in the future.

This report details phase one of this project with the thematic analysis of the findings from the three workstreams- systematic evidence reviews; a synthesis of patient, carer and staff surveys and a survey of ongoing evaluations.

About the Project Partners

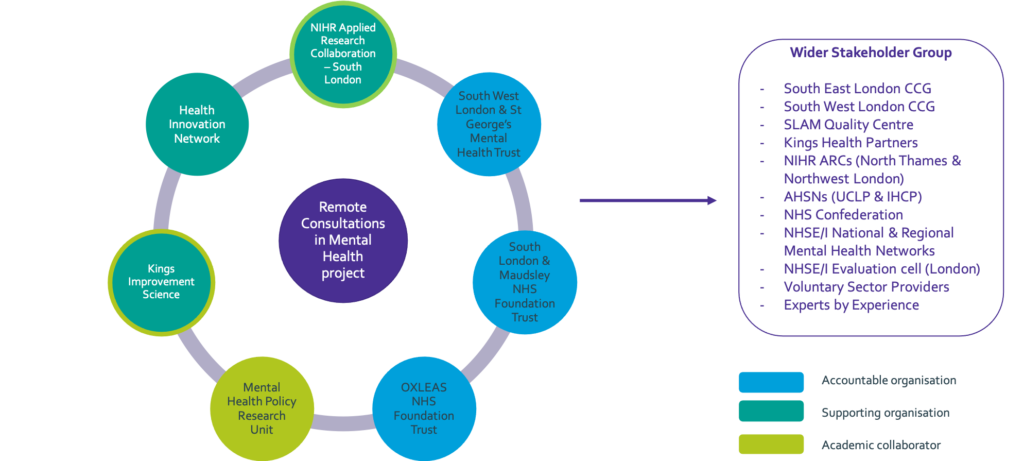

This work is produced jointly by the following organisations. The group have formed as the MOMENT (reMOte MENTal health group).

The Health Innovation Network

The Health Innovation Network (HIN) is the Academic Health Science Network (AHSN) for south London, one of 15 AHSNs across England. As the only bodies that connect NHS and academic organisations, local authorities, the third sector and industry, we are catalysts that create the right conditions to facilitate change across whole health and social care economies, with a clear focus on improving outcomes for patients. This means we are uniquely placed to identify and spread health innovation at pace and scale; driving the adoption and spread of innovative ideas and technologies across large populations.

The NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London are a research organisation that brings together researchers, health and social care practitioners, and local people to improve health and social care in south London.

Kings Improvement Science

King’s Improvement Science (KIS) comprises a small team of researchers and quality improvement experts. Their aim is to help improve health services in south-east London.

Expert by Experience group

A group of four Experts by Experience with a range of backgrounds including experience of using health and social care services and caring responsibilities were recruited by the KIS Patient and Public Involvement Coordinator through the KIS involvement bulletin. The group have been core team members throughout the programme from September 2020.

Mental Health Policy Research Unit

The aim of the Mental health Policy Research Unit is to help the Department of Health and others involved in making nationwide plans for mental health services to make decisions based on good evidence. They make expert views and evidence available to policymakers in a timely way and carry out research that is directly useful for policy.

South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust

South West London and St George’s (SWLSTGs) serves 1.1 million people across the London boroughs of Kingston, Merton, Richmond, Sutton and Wandsworth and employ more than 2,000 staff who provide care and treatment to about 20,000 people from south west London.

Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust

Oxleas provide a wide range of health and social care services to people living in south east London and parts of Kent. This includes physical health, community services and mental health care such as psychiatry, nursing and therapies. Oxleas have 4,000 members of staff working in many different settings, such as hospitals, clinics, prisons, children’s centres, schools and people’s homes.

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) provides the widest range of NHS mental health services in the UK. They also provide substance misuse services for people who are addicted to drugs and alcohol. Their staff serve a local population of nearly two million people. They have more than 230 services including inpatient wards, outpatient and community services. They provide inpatient care for over 5,000 people each year and treat more than 45,000 patients in the community in Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon. They also provide more than 50 specialist services for children and adults across the UK and beyond.

South London and Maudsley Quality Centre

The SLaM Quality Centre Improves mental health care for the populations they serve using data, evidence-based planning, care process models and a shared methodology. The Quality Centre defines, tests, implements and continuously improves the work of the Trust, so that service users, carers and staff can clearly see what is expected at each part of a journey through the system. This is being achieved through the collaboration of our clinical, academic, lived experience (service user and carer), quality improvement, operational, governance and commissioning leads.

Foreword

The new coronavirus SARS-CoV2 was first identified in late 2019 with the first cases of COVID-19 infection reported in the United Kingdom at the end of January 2020. From mid-March 2020 onwards, social distancing measures were introduced to reduce the spread of the virus and health services rapidly increased their adoption of remote consultations. This included inter-professional, service user and carer facing interactions using the internet, telephone, video conferencing and text messaging. Video conferencing software called ‘Attend Anywhere’ was made freely available to secondary care from 31 March 2020.

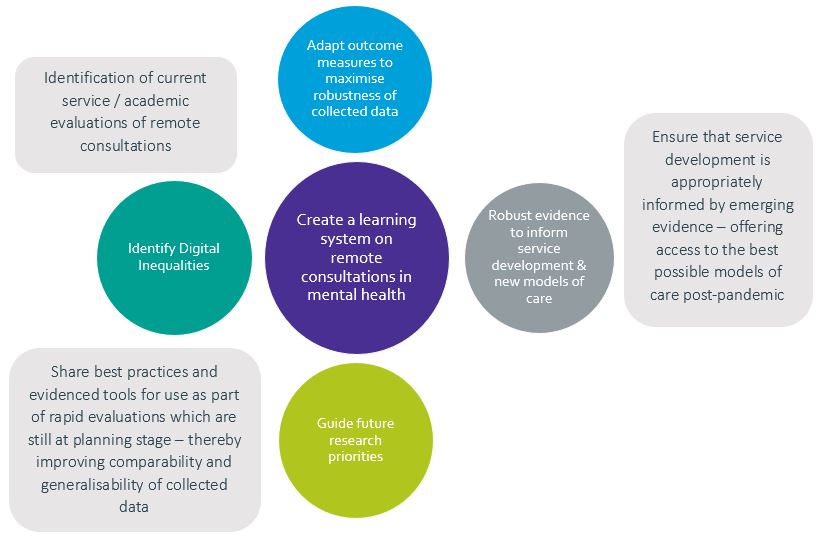

In response to this rapid change, a number of partners across south London mental health service providers, service users, service and innovation connectors and academic evaluators came together with the ambition of forming a learning health care system[1] to evaluate experiences, implementation, and effectiveness of remote consultations in the context of existing and emerging evidence to inform and improve service delivery, during the pandemic and beyond.

Our interested organisations joined in June 2020 as an informal partnership across south London. Together we identified and agreed on a programme as part of COVID-19 response work. Phase one saw the delivery of a survey of ongoing evaluations being conducted in south London; a synthesis of patient, carer and staff surveys; and systematic evidence reviews.

Phases two and three were centred around the dissemination of our findings and establishing a ‘Learning Healthcare System’ on remote consultations in mental health settings.

This local-level learning has the potential to be captured, synthesised and shared across organisations; to identify evidence gaps, create positive change within services and improve experiences and outcomes for patients, carers and staff. This report shares our methods, findings and tools developed and highlights the gaps in evidence and future research opportunities. Please stay up to date with our work develops via our webpage and use the contact form to get in touch with the team.

Professor Fiona Gaughran – Lead Consultant Psychiatrist, National Psychosis Service, Director of Research and Development SLAM, Reader in Psychopharmacology and Physical Health Kings College London, Applied informatics research lead NIHR ARC South London

[1] The concept of a healthcare system collectively gathering information and synthesising knowledge about how well or otherwise service delivery is working then using this understanding to drive ongoing improvement can be described as a ‘learning healthcare system’. The Institute of Medicine defines a learning healthcare system as a system in which “science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.”

Background

Service changes were introduced extremely rapidly across the NHS in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including in mental health. These included a shift from face to face service delivery to a model where most outpatient contacts were conducted remotely, either on the telephone or by video consultation. These service changes may have significant advantages for many staff and patients, such as convenience, safety, time savings; they may also have disadvantages, drawbacks, or unintended consequences, and may exclude some key populations.

Our partnership sought to understand the impact of such service changes, what has worked and what has been less successful, and for whom, in order to either embed or adapt, new and emerging models going forward, to ensure the greatest benefits for patients, carers and staff. This report also provides case studies that describe the implementation processes that supported the introduction of these novel models of care in the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The project is set mostly in south London and includes the three mental health Trusts – South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust (SWLSTG) and Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust (Oxleas), working closely with the Health Innovation Network (HIN), Kings Improvement Science (KIS), NIHR ARC South London and the SLaM Quality Centre (a collaboration between the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN) at Kings College London (KCL) and Kings Health Partners (KHP) along with the Mental Health Policy Research Unit. University College Health Partners (UCLP) were also involved in the partnership contributing to the core group and sharing the e-survey across their mental health providers in north east and north central London.

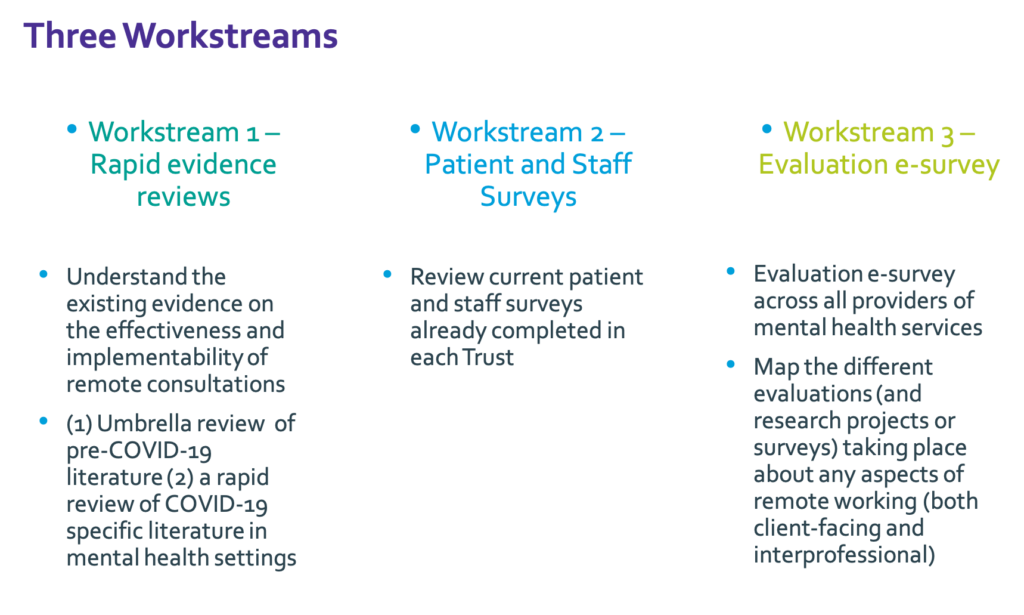

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Aims

To bring together the findings from the three workstreams to inform clinical practice and to determine ongoing gaps in knowledge. The workstreams are listed below.

- Systematic literature reviews of the evidence on remote consultations pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Thematic synthesis of Trust-wide surveys on remote consultations

- E-survey of projects on remote consultations across south London mental health NHS Trusts

The specific objective of this work was to identify commonalities and areas of difference; highlight gaps in the evidence base around remote consultations in mental health services that may need to be addressed in future research, and inform future information gathering approaches. The evidence gathered supports mental health services and service users to learn what is already known about remote consultations.

Figure 3:

Methodology

Partnership development

Our interested organisations joined in June 2020 as an informal partnership across south London. Together we identified and agreed on a programme of work as part of COVID-19 response work. The group have formed as the MOMENT (reMOte MENTal health group).

Programme methodology

A project group was established with resources, timelines, and a governance structure across the multiple partners. A project plan and data capture process were established and a forum (the core group) that allowed sharing of tools and approaches. A dissemination plan and engagement strategy were written to connect with colleagues across London and help create a larger learning network. A group of four experts by experience with a range of backgrounds, including experience of using health and social care services and caring responsibilities, were recruited by the KIS Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) Coordinator through the KIS involvement bulletin. The project group used the learning health system as an organising framework and co-designed the work programme with providers, users, and evaluators.

Programme structure – The programme was split into three workstreams.

- Workstream one – Evidence reviews

Two reviews were conducted. One ‘Umbrella Review’ on the evidence pre-COVID-19 and a systematic review of evidence during the pandemic

Umbrella review

We conducted an ‘umbrella review’, also known as a ‘review of reviews’, of research literature and evidence-based guidance on remote consultations in mental health, including both qualitative and quantitative literature, conducted and published prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim was to identify the pre-COVID-19 literature on guidance, effectiveness, implementation and economic effectiveness of remote consultations in mental health. Nineteen reviews met our criteria, reporting on 239 studies and 20 guidance documents. The review included studies on telephone counselling, videoconferencing for diagnosis, therapy and education across a range of diagnoses.

Systematic review

We also conducted a systematic review of the evidence on remote consultations in mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our aims were to identify the adoption and impact of remote “telemental” mental health approaches and facilitators or barriers to optimal implementation. Seventy-seven relevant papers were synthesized.

- Workstream two – Trustwide patient and staff surveys on remote consultations

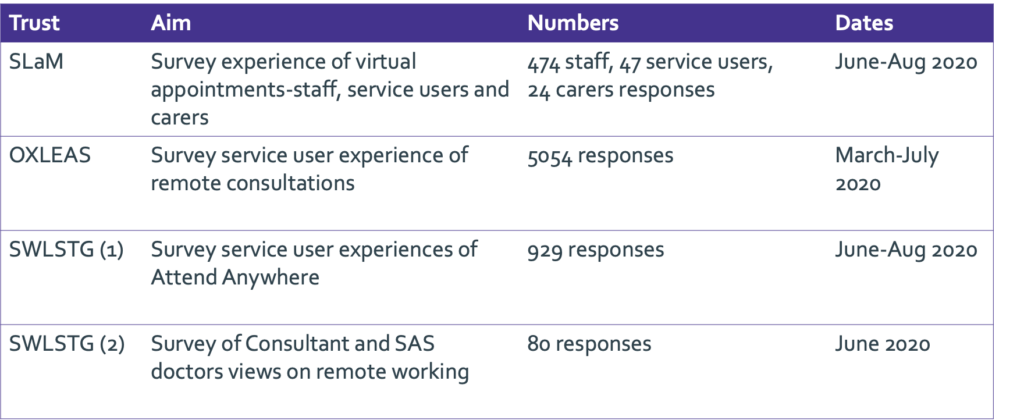

A thematic analysis was conducted to synthesise the questions and findings across four organisation wide surveys that were carried out within the three south London mental health Trusts in the summer of 2020. This analysis included results from patient and carer surveys, one survey of Consultants and Specialty and Associate Specialty (SAS) doctors, and one survey that collected responses from patients, carers and staff (see table one). Please see here for copies of each individual survey report.

Table 1:

- Workstream three – e-survey

An electronic-survey (e-survey) (Appendix one) was conducted to collect information about evaluation, research or quality improvement projects studying any aspect of remote consultations (both patient-facing and interprofessional) within mental health services. The survey was initially conducted within the three mental health Trusts in south London, though some of the projects described were in local voluntary sector organisations or had national / international reach. The survey was then carried out in north east and north central London following minor modifications.

The focus of the survey was to collate information about project aims and methods; we did not capture findings.

The south London e-survey was initially open to responses between 13th July 2020 and 1st September 2020 and was briefly electronically reopened on 11th November 2020 to allow entry of five additional projects that became known to members of the project group. In north east and north central London the e-survey was open between 5th October 2020 – 15th November 2020.

Summary of findings

Triangulation of evidence and data: A thematic analysis of the findings from the three workstreams was undertaken by a multidisciplinary team of researchers and project managers, further scrutinised by a team of experts by experience, and by clinical and managerial members of the project group. An infographic summarising the findings from this analysis is being developed by the experts by experience (underway).

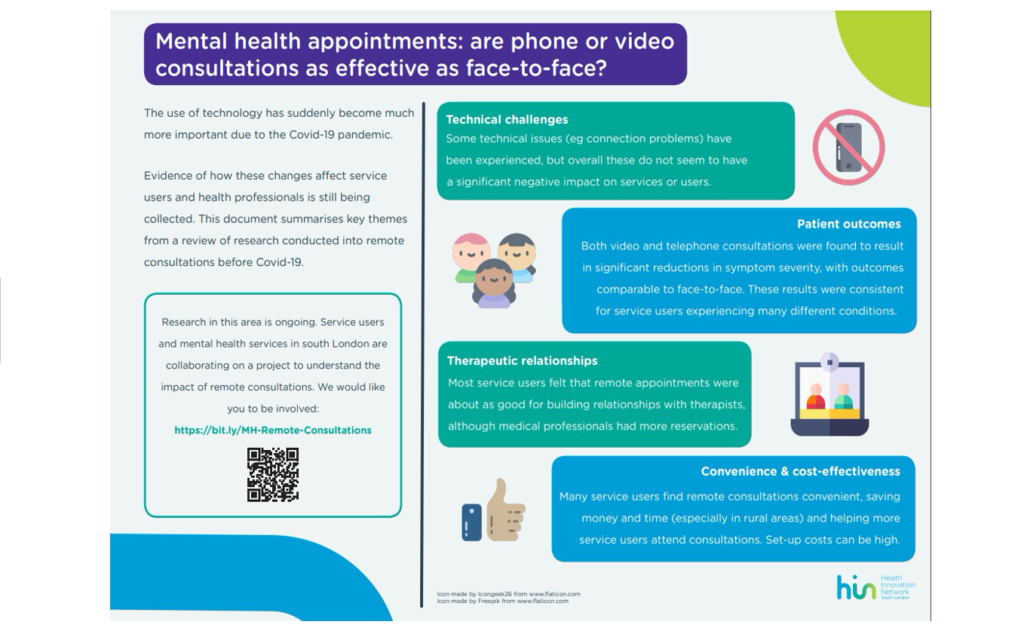

Workstream One: Evidence reviews

Umbrella review of pre-COVID-19 literature- Please see [https://www.jmir.org/2021/7/e26492] to access the paper.

This systematic review of systematic reviews revealed the following:

- Remotely delivered mental health services can be as efficacious and acceptable to staff and patients as face-face formats, at least in the short-term.

- There was little evidence on large scale implementation of remote consultations and effectiveness in ‘real-world’ (i.e. outside of a research study) settings.

- Further, the findings of this umbrella review did not provide us with evidence relating to digital exclusion and how it can be overcome and was not able to provide conclusions on particular contexts, for example children and young people’s services or inpatient settings.

A systematic review of COVID-19 literature from during the pandemic– (link will be added to paper when available)

A synthesis of 77 relevant papers from 19 countries demonstrated that globally, many countries had been able to rapidly shift to remotely delivered mental health services during the pandemic. In general, these studies suggest that:

- Telemental health has been reasonably well accepted, particularly where the alternative was no contact.

- A mixture of telephone and video-based calls have been offered, with people expressing different preferences for these.

- Concerns about remotely delivered services are raised in relation to new service users, physical healthcare, and privacy and confidentiality.

- A small number of studies have formally investigated how telemental health may best be implemented, though suggestions made within this body of literature to support implementation include:

- Staff training, champions for telemental health, providing service users with access to technology and guidance on how to use it

- Providing staff with guidance on identifying whether a remote offer is appropriate in different situations / with different individuals.

Overall, the literature suggests that the delivery of telemental health has been largely successful within the context of a pandemic. Nonetheless, longer-term evaluation and better evidence is needed as restrictions on physical distancing between people evolve.

Figure 4:

Workstream two: Summary of findings from the Trust patient and staff surveys

Patient experience of remote appointments can be summarised as follows:

Oxleas:

- 90% of patients responded “Yes” or “Somewhat” when asked if they were happy with the care and treatment received in their remote appointment.

- 79% of patients responded “Yes” or “Maybe” when asked if they would like to be able to have remote appointments in future.

SWLSTGs:

- 97% of survey participants reported that they would either ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ use the system again, were they to be offered the option, despite issues with video and audio quality reported in the survey.

Joint patient and staff survey at SLaM:

From responses to a question on experience and one on future intent, three profiles of virtual contact users was constructed.

• Resistant (n=84): those who reported that their virtual contact experience was “worse/ much worse” than that in face-to-face contact, and they are “somewhat/ very unlikely” to want it in the future

• Ambivalent (n=338): those who did not find virtual contact experience better than that in face-to-face contact, yet they showed no intention to reject it in future

• Receptive (n=123): those who found virtual contact “better/ much better” than face-to-face contact and are “somewhat/ very likely” to want it in future More detailed information on each of the surveys is included in table two in the appendix.

The themes produced were considered according to whether the survey responses had been collected from patients or staff.

The following themes were generated, a range of opinions were expressed in relation to each theme.

- Convenience.

- Environment and privacy.

- Choice.

- Openness during consultations.

- Limitations compared to face-to-face.

- Longer-term use.

- Resources required for better implementation.

The analysis of themes across all the surveys is listed in table three in appendix two.

Important gaps in the information available following the thematic synthesis were identified.

- There was a lack of demographic information about participants. Considering the information about respondents that was available and combining this with knowledge about the survey sampling and distribution methods, we are able to conclude that respondents are not representative of the population and as such the findings of the thematic analysis may not be generalisable

- We also recognise that the surveys were designed to capture a snap-shot of perspectives at a particular point in time within the context of a pandemic and that view-points shift over time.

Convenience

“Would prefer to use this system rather than face to face. It is more convenient for me as I work full time and means I do not have to leave work early”

South West London & St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust

“Logistically more convenient, no travel expense and in an era of COVID-19, feels safer.”

“Benefits: less travelling time, more productive”

OXLEAS

Benefits: less travelling time, more productive

“Easier to manage work life balance, less tired as reduced travel”

South West London & St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust

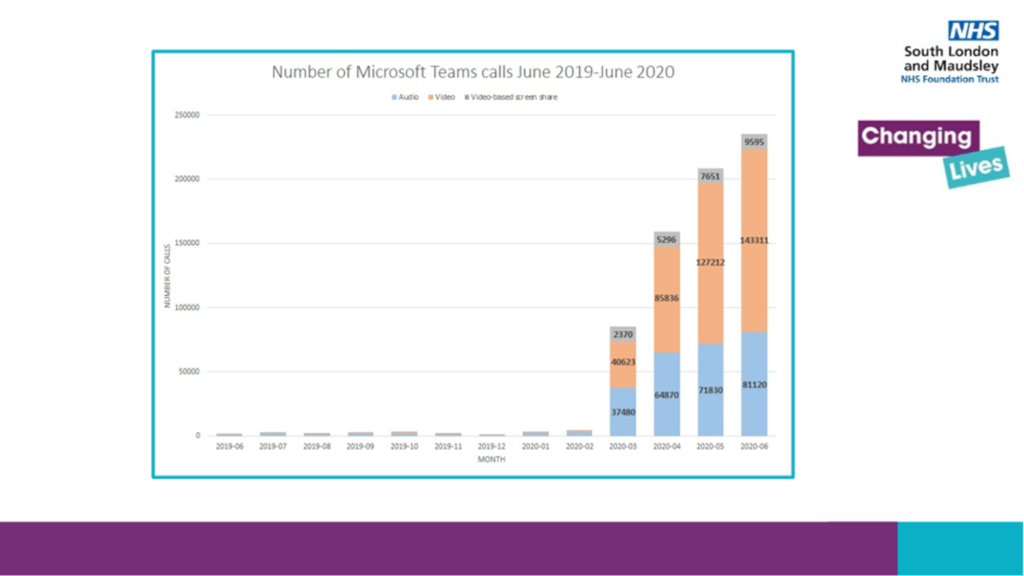

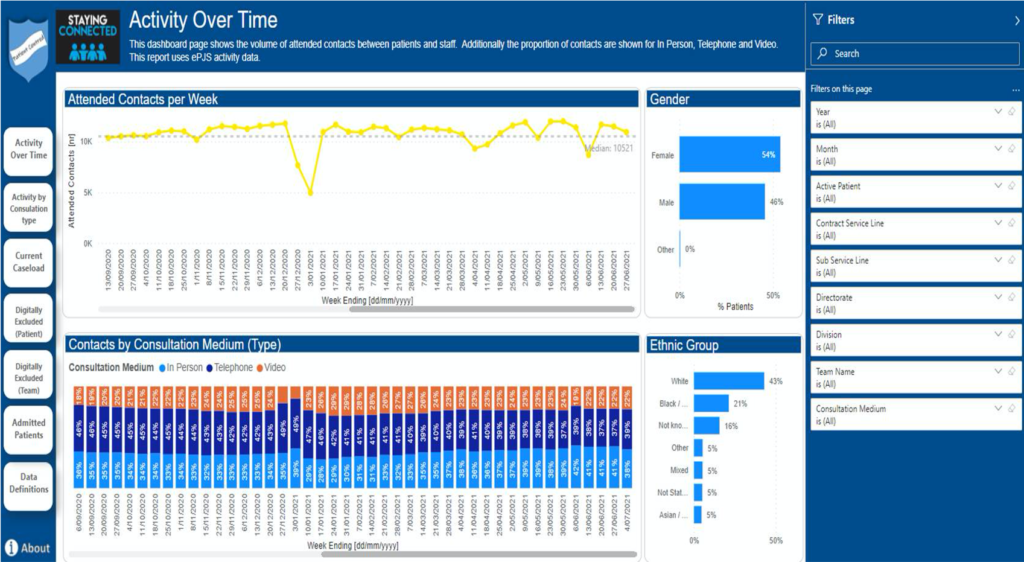

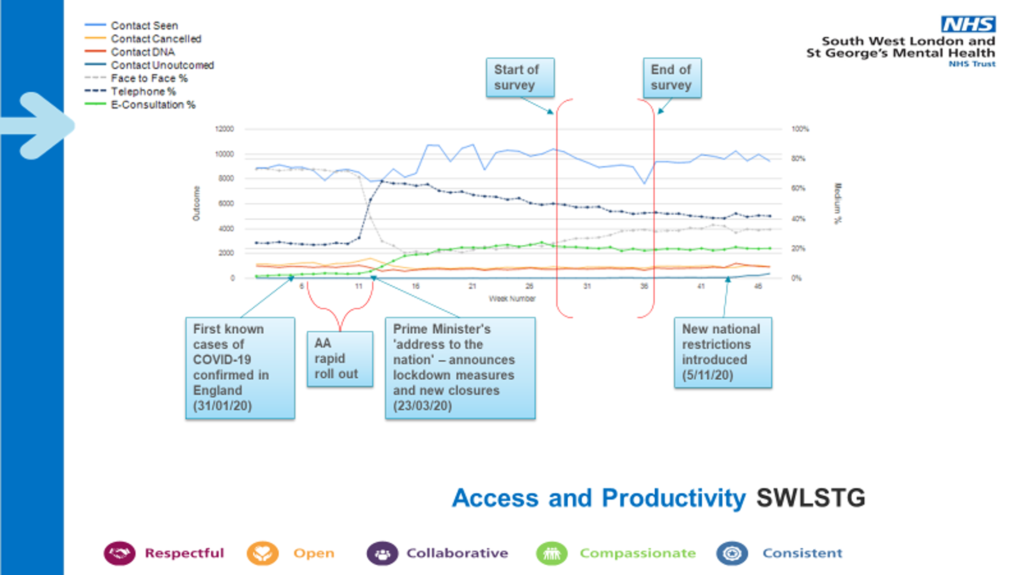

Making best use of data – improvement analytics

In addition to the Trust surveys, both SWLSTG and SLaM rapidly developed dashboards to track access and productivity to remote consultations over video, in person and telephone. You can view a case study from SLaM here.

Improvement analytics supports delivery of a Trust Data Strategy where the Trusts aim to become a data-driven organisation, where all staff have the capacity and ability to use data to inform decision-making and improvements in order to improve outcomes for the patients and communities.

This includes:

- Visualisation of data for improvement

- Diagnostic data

- Measurement plans

- Power Business Intelligence dashboards

- Data for improvement resources and coaching

These dashboards provide visualisation of data which is intended to be the foundations of a conversation starter.

Please see Figure five and six for snapshots of the dashboards. The SWLSTG dashboard shows the increase in telephone and video consultations from the point of the first lockdown. It also illustrates the time period of the patient survey described in workstream two.

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Workstream three: Summary of findings from the E-survey

Responses

Responses from south London based mental health organisations described 22 projects. A further 10 projects being conducted in north east and north central London were captured by the survey. The findings describe all 32 projects (please see appendix two for more detail on each project).

Focus of projects

The majority of projects (29 out of 32) sought to assess patient and/or staff perspectives on experience and/or access via surveys or interviews.

Design and methods

There were 16 service evaluation projects; five quality improvement projects; five service evaluation and quality improvement projects; five research projects; and one strategy discussion.

The broad methodological approaches being used are: qualitative, e.g. interviews/focus groups (three projects); quantitative, e.g. analysis of routinely available data (one project); survey (20 projects); mixed methods (7 projects), unclear (1 project).

Patient and public involvement within the projects:

Just over a third of projects (11 out of 32) stated intention to involve their patients/public members within the project team, for example in aspects of project planning and delivery, as opposed to involving patients/service users/carers as participants in the project.

Service areas and patient groups:

A range of service areas and patient groups are included across the 32 projects.

Some projects span multiple services, others are Trust (or organisation) wide.

Demographics:

Under a third (nine out of 32) demonstrated intention to collect demographic information from participants. This is potentially an important gap in terms of better understanding for whom remote consultations does and does not work well for.

Remote consultations technology: type, function and support

Many projects included the use of multiple types of phone or video-based technology within their questions / data collection. Technology solutions specified included:

Microsoft Teams and Zoom were the most mentioned platforms.

Across the 32 projects, remote consultations was listed as being used to facilitate:

• Individual assessments

• Routine clinical appointments

• Individual psychological therapies

• Group psychological therapies

• Online arts psychotherapy

• A listening service

• Emergency appointments

• Patient reviews

• Interprofessional communication and administration including meetings

• Service evaluations & surveys

Respondents were asked whether support is offered for remote consultations to staff and/or patients (e.g. training, introductory video, or technical assistance). Some respondents left this question blank or indicated that no support is offered. Where it was indicated that support is available, this took the form of webinars; patient leaflet / instructions; informal training from staff (unclear whether this relates to staff-to-staff or staff-to-patient), support for staff from Attend Anywhere Team; and staff supporting patients to complete e-surveys.

Questions about preferences or comparisons between different remote consultations platforms are included within ten projects. In addition, nine projects will collect information about technical issues (e.g. hardware, connectivity, inter-operability) or anticipate that this may emerge within qualitative findings

Outcomes being studied:

A minority of projects (four out of 32) were set to assess the effectiveness of remote consultations on clinical outcomes or examine cost. None of the projects were assessing cost effectiveness.

Very few respondents gave clear details of service level outcomes (for example relating to numbers of patients supported or impact on team working) assessed within their projects, though one project will collect service level data on Did Not Attend (DNA) rates and travel.

Participants were asked what (if any) implementation outcomes (e.g. acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, sustainability) are being studied and how these are being measured or assessed. Nine projects will assess one or more implementation outcomes via qualitative interviews or surveys with acceptability being mentioned most frequently (four projects). It is unclear whether any of these projects intend to use validated scales to assess implementation outcomes.

A minority of projects assess unintended outcomes (positive or negative) or inequities (for example characteristics of or number of people not accessing remote care).

Theories and frameworks:

The majority of respondents did not report applying a specific framework, theory or model to guide their reported project.

Potential gaps in research and evaluation:

Several topic areas are not well covered by the 32 projects and are potentially under-researched or evaluated:

- Contextual details including numbers of patients in contact with services; the proportion of contacts delivered remotely versus face to face; the characteristics of patients who are (or aren’t) accessing services in different ways; and how each of these variables are changing over time

- Digital exclusion / inequities and gaining an in-depth understanding of which groups of people are not well served by remote consultations

- Patient and public involvement in designing and executing projects

- Understanding impact on staff interprofessional working

- Evaluating the support offered to facilitate remote consultations (e.g. training, webinars, patient leaflets)

- Effectiveness studies looking at clinical outcomes

- Cost effectiveness of remote consultations

- Evaluating implementation of new pathways including hybrid/blended approaches to service delivery (a mix of face-to-face and remote delivery) and de-implementation of old ways of working

- The use of implementation frameworks / theories / models to understand, contextualise and generalise project findings

However, it should be noted that many of the above topics are indeed touched upon or may emerge as areas of exploration or as findings within some of the projects, particularly within those projects that are collecting qualitative data from participants.

Limitations of the e-survey:

The e-survey provided a snapshot of projects planned or underway between July and November 2020. Many projects will have been instigated subsequently.

While every effort was made to disseminate the survey widely across the eligible mental health services, we are aware that some relevant projects already underway were missed.

While a small number of responses were received from charitable / voluntary sector organisations, there is likely to be a body of work being undertaken by such organisations that is not captured here.

The survey distribution method used by each organisation did not follow a uniform approach. It is possible that some distribution methods were more effective than others in reaching the relevant people and encouraging project leads to complete the survey. Direct email contact with individuals known to be engaged in relevant projects appeared to be the most successful way to encourage survey completion.

It would have been helpful to obtain more detail about the methods being used within each project, and any repeat surveys in the future should include questions that would elicit this information. For example, where it is indicated that the project involves a survey, we do not have detail about whether the survey was distributed in an electronic (e.g. email or text) or paper format and we often do not have information about the types of questions asked.

The questions on service outcomes, implementation outcomes and unintended consequences were frequently left blank by respondents, potentially indicating that participants did not understand what the question was asking or that they felt it was not relevant to their project. It would be useful to obtain feedback on the survey questions from staff members should the survey be repeated. Furthermore, in future iterations it may prove helpful to follow up each response via telephone interview, allowing exploration of questions where limited detail was initially offered.

It is possible that the methodological quality of future projects could be strengthened by providing team members with training or relevant resources on implementation.

The original aspiration was to embed patient and public involvement within this piece of work. The short timeline meant that it was not possible to involve public members within the development of the e-survey, however, the findings have been discussed in group meetings which include experts by experience.

Commonalities across workstreams and recommendations

The following themes emerged from the three workstreams and are inter-related.

Perspectives are not universal

Our collective findings across the workstreams clearly demonstrate that there are a variety of perspectives regarding remote consultations between staff and patients, and regarding remote consultations more broadly (including staff inter-professional working).

The remote delivery of mental health services works well for some people but not others and is appropriate in some situations or on some occasions but not others for many individuals. There is no ‘one size fits all’ and an individualised approach will always remain the gold standard. This breadth of experience holds true for patients, carers, and staff.

It follows that the effectiveness of remote consultations on a range of outcomes – for example clinical symptoms for patients, or wellbeing or productivity for staff – may not be universal either; this too remains to be established.

Recommendation: Further research is required to better understand under which circumstances remote consultations is beneficial, for whom, and why, in order to make evidence-informed offers regarding the mode of service delivery and to provide increased choice. This research should purposively seek to tap the views of under represented populations e.g. racial and ethnic minority groups, carers and do deep dives within clinical populations.

Acceptability

Findings from our thematic analysis of the organisation wide surveys mirror findings from our two literature reviews in terms of the acceptability of remote consultations to patients, carers and staff. Both workstreams suggest that while there are different opinions, and while face-to-face contact may be preferred, remote service delivery can be acceptable to patients, carers and staff, at least in the short-term, with many participants indicating that they are satisfied with this way of working. Levels of satisfaction may be higher when video calls are used as opposed to telephone calls. It is noteworthy that the pre-COVID-19 review indicates that these findings may apply outside of the context of a pandemic. Again, findings from the staff and patient surveys, in particular, illustrate the point that individuals may find remote working and/or remote consultations acceptable on some occasions / in some circumstances but not others. Furthermore, the likelihood of non-response bias (where people who take part in a study are systematically different to those who do not) is a key caveat here as participants across workstreams were firstly able and secondly motivated to engage in research and provide their feedback or data may not be representative of wider populations.

Recommendation: A set of questions to be routinely asked as part of future projects should be developed. As an example, questions should elicit participants’ demographic information in order to better understand whose perspectives and data are being captured or excluded. This would help us to understand whether there may be differences according to ethnicity or living in an area of relative deprivation/advantage, for example. This work has commenced by the project team please check for updates.

Recommendation: Future research and evaluation strategies should specifically target the groups who have been under-represented in the data sets analysed to date, including but not limited to: older adults, children and young people, people with learning disabilities, people with an autism spectrum disorder, inpatients, drug and alcohol clients, prison leavers, homeless people and carers.

Accessibility

For many people, for example, those with diverse communication needs, the widespread adoption of remote technologies at the start of the pandemic removed choice and reduced the ability to access mental health services. Findings from the staff and patient surveys demonstrated that some patients had received text messages inviting them to a video-based consultation and including a link to join the virtual meeting without any prior conversation about whether this format was appropriate for their needs. Similarly, some consultations were offered via telephone without assessment of whether this was an appropriate means of communication for individual patients and carers. There are also some good examples of services using innovative ways to engage service users in remote consultations – (Click here to see how the Recovery College at SWLSTGs have supported their students in accessing resources remotely and here to see how SWLSTGs have assisted their patients and carers in accessing Attend Anywhere via a step by step video guide) – and where guidance was produced to help clinicians with decision making tools for choosing between remote, in person or blended consultation.

Recommendation: Organisations and services should ensure that the NHS Mandatory Accessible Information Standards are adhered to when offering remote consultations or indeed when staff are engaged in remote work more broadly. We need to be asking service users and carers about their capabilities and confidence and addressing this.

Convenience

Three of the systematic reviews included within the pre-COVID-19 umbrella review assessed convenience, with most patients indicating that engaging with therapy sessions from home via remote interventions was convenient. Convenience was also a main theme arising from the thematic analysis of survey findings. Many respondents highlighted the convenience and time and/or money saving nature of remote consultations or remote work by virtue of not needing to travel. Further, some people felt that remote appointments could facilitate the attendance of more people from a multi-disciplinary team, though others suggested the opposite was true. Importantly, however, there was a consistent message that some people find remote consultations (or for staff remote work more broadly) inconvenient some or all of the time. Patients cited difficulties with computer literacy, having an appropriate private space, involving family members or carers in appointments where this was wanted, and poor virtual meeting etiquette (e.g. being left in ‘waiting rooms’ for lengthy periods). Staff also noted problems with meeting etiquette (e.g. meetings over-running), unsuitability of the environment for privacy and ergonomic reasons, and the tiring nature of virtual meetings.

Therapeutic alliance

Findings from both the staff and patient surveys and the evidence reviews suggested that for some people it is possible to develop a good therapeutic alliance remotely, although it is perceived that therapeutic alliance may be better when services are delivered face-to-face. In our pre-COVID-19 umbrella review, female older adults and veterans generally expressed a preference for talking to therapists in person. One of the studies included in the during-COVID-19 systematic review reported that 88% of clinicians found it more difficult to establish a therapeutic relationship with new clients when consultations were held remotely. Similarly, two systematic reviews within the umbrella review included findings demonstrating poorer clinician ratings of the therapeutic alliance during remote work. There was some suggestion that therapeutic alliance may develop more easily in consultations held using video-conferencing software as opposed to the telephone.

Technological challenges

Within our patient and staff survey findings, specific issues relating to the use of technology included: user confidence and knowledge around using technology, issues with Wi-Fi and connectivity, ability to access (and cost of) appropriate equipment and software subscriptions, and security/information governance challenges. Having access to technology and appropriate support to use this technology were identified as key barriers to uptake. These findings applied across patients, carers and staff. Within our umbrella review, three of the systematic reviews included mentioned technical difficulties as a challenge, however, none of these reviews implied that technical difficulties had been a severe barrier to implementation. However, issues were reported around mistrust in technology, low image resolution, and connectivity problems.

Exclusion

Findings across workstreams raise the possibility that many people may have been excluded from accessing mental health services with an impact on their wellbeing and their families, or have had their access reduced, as a result of the rapid shift to remotely delivered services. This is mirrored by the presumed exclusion of people who are not routinely using remote technologies from much of the research and evaluation data that have been analysed to date. However, we do not have systematically collected data to demonstrate the extent of digital exclusion or to draw conclusions about which groups of people are most adversely affected. There are a small number of projects (that we obtained details of via the e-survey) that are seeking to understand the perspectives of some of those groups who are more likely to be digitally excluded (for example people with learning disabilities and older adults). Within our staff and patient survey synthesis, it was recognised that the perspectives of older adults are mostly unknown. While the umbrella review included data relating to some groups who are thought more likely to be digitally excluded (e.g. older adults) there was a lack of evidence for other groups including children and young people and inpatients, and overall, as outlined above, a lack of demographic information about people who had participated in the research studies (which was also a key limitation within the e-survey and evidence reviews).

Recommendation: The co-creation of research/evaluation and service delivery strategies to help understand and address digital exclusion and inequities will be vital and careful consideration will need to be given to assess how best to involve those who are under-represented and/or digitally excluded within the development of these strategies. Engagement from a variety of services, for example, assessment centres, food banks, probation services, supported accommodation and community charities may be needed to reach those who are under-represented. It is acknowledged that this work would be challenging, but it will be essential for services where digital is the primary route to care.

Guidelines

Responses to staff surveys synthesised indicated that staff would appreciate clear guidelines on how and when to offer remote consultations as opposed to face-to-face. This was echoed in the during-COVID-19 literature review. Our umbrella review included one systematic review of guidelines for video-conferencing based mental health treatments[1]. This review encapsulates guidance on decisions about the appropriateness of remotely delivered mental health services; ensuring competence of mental health professionals; legal and regulatory issues; confidentiality; professional boundaries; and crisis intervention.

Recommendation: It may be beneficial for those who are developing new guidance on video-based consultations within mental health services to draw upon the recommendations made within the systematic review by Sansom-Daly et al. (2016).

Case studies

Remaining research and evaluation gaps

Reaching those who are least able to engage in remote consultations

All three workstreams likely under-represent the voices of those who are least likely and able to engage remotely which represents a significant and worrying gap in the available evidence. Data collection mechanisms to date have been overly reliant on electronic means – for example surveys administered by email. Innovative methodologies will be required to proactively reach digitally excluded people and enable their participation in both developments of a research strategy and in the research itself, especially under the restrictions in movement and socialisation placed upon the population during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uptake

Some of the data considered within this project suggest that the offer and uptake of remote consultations varies according to service. Further work could be done to understand the reasons underpinning choices made by services and differences in uptake amongst different patient groups. The routine collection of data relating to the mode of service delivery over time in each clinical pathway would likely form an important next step in the development of a ‘learning healthcare system’ that collectively gathers information and syntheses knowledge about how well or otherwise service delivery is working then uses this understanding to drive ongoing improvement.

Change over time

We are currently unable to draw conclusions about whether perceptions in relation to remote consultations are changing over time nor whether viewpoints will evolve as we move beyond the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and towards a situation where face-to-face contact poses less risk of spreading infection. Longitudinal data are needed to inform future choices and investments. The most rigorous way to assess change in perceptions and experiences over time is to ask the same set of people the same questions repeatedly. This requires each participant to have a unique anonymous identifier assigned to their survey responses in order to track change over time. This methodology is often more time and resource intensive to set up, and the attrition rate (where people drop out / don’t complete surveys) may be high. Further, people who are motivated to participate in completing a series of surveys may have different characteristics or perceptions compared to people who do not participate.

Blended models of service delivery

We currently know very little about models of delivery, experiences and effectiveness of mental health services that are delivered through a combination of remote and face-to-face consultations.

Recommendation: Research is needed to evaluate the implementation of new pathways including hybrid/blended approaches to service delivery (a mix of face-to-face and remote delivery) and de-implementation of old ways of working.

Effectiveness

While the pre-COVID-19 umbrella review demonstrated that remotely delivered services can be as good as face-to-face appointments in improving clinical outcomes in some circumstances, we cannot say with certainty whether this finding holds true in the case of fast and widespread implementation due to the pandemic, as there was a lack of high quality quantitative evidence within our during-COVID-19 literature review .

Recommendation: It is important that future work addresses questions of clinical effectiveness and better ascertains for which groups of people and which clinical pathways remote consultations are and are not effective before being routinely offered as the norm post-pandemic.

Cost and cost effectiveness

Given the relative dearth of evidence on the effectiveness within the pandemic context, it follows that little is known about the cost effectiveness of remotely delivered mental health services. Within our umbrella review, two systematic reviews examining either costs or cost effectiveness met our inclusion criteria. One systematic review concluded that tele-psychiatry can be cost effective compared to face-to-face interventions, particularly in rural areas where the number of consultations required before telepsychiatry becomes more cost effective (combatting initial equipment costs) is lower. In the second systematic review which looked at costs, 60% of included studies reported that telepsychiatry programmes were less expensive than in person care, due to savings such as travel time and reduced need for patients and their families to take time off work. However, eight studies in this review concluded that telepsychiatry programmes were more expensive, particularly due to videoconferencing equipment costs. A final study included in the review found no difference in costs.

Recommendation: Further research regarding costs and cost effectiveness is needed, particularly as video-conferencing software is now more widely and cheaply available.

Implementation effectiveness and support

Our COVID-19 specific literature review had a focus on exploring barriers and facilitators to optimal implementation of remote consultations and the emerging evidence on this is summarised. the pandemic led to remote consultations and remote work being implemented urgently as a matter of need and not choice. This presented little chance to study implementation effectiveness in real-time, thus work remains to be done to establish best practices in terms of implementing remote consultations. Such studies are now feasible as remote options are likely to be offered long-term in some settings. The existing implementation science literature may be helpful in designing better implementation support going forward. Furthermore, we may be able to apply frameworks retrospectively in order to generate additional learning from implementation efforts undertaken within the context of a crisis.

Next steps

The programme has achieved a great deal since June 2020 and the work continues using the Learning Healthcare system model as our guiding principle.

Evaluating remote consultations is a priority for the London Healthcare system. Research resource is being established for this for the NIHR Applied Research Collaborations (NIHR ARCs) that we hope will continue to inform our work.

Acknowledgements

Appendix one: The south London e-survey (workstream three):

Evaluations on remote working in mental health services in South London

What is the project about? Our trust is working to understand the impact of remote working during COVID-19 on staff and patients. We want to map the different evaluations (and research projects or surveys) taking place about any aspects of remote working (both client-facing and interprofessional). By combining this information, we can better learn and plan for COVID-19 recovery. This information will be collated across South London mental health trusts who are working in partnership supported by the Health Innovation Network, NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London and King’s Improvement Science. This will allow rapid action learning back to improve patient care. What am I being asked to do? Please let us know about any evaluations (past, current or planned) that are looking at different ways of working with patients, carers, families or colleagues, since the beginning of the pandemic.

The aim is not to interrupt/change what you are doing, it is simply to map what is going on. Please also share any documentation (e.g. survey questions, topic guides, protocols) that can provide more detail about the evaluation. This can be emailed to Dr Lucy Goulding, Programme Manager at King’s Improvement Science on lucy.goulding@kcl.ac.uk. The survey should take approx 15 min to complete and closes on 21st August. How will personal data be used? All data will be managed in full compliance with the Data Protection Act 2018 and General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) 2016. All information you share will be stored on a secure server, will only be seen by the core project team from the partners organisations, and only used for the purposes of the mapping exercise. Non-personal data will be analysed and anonymised findings may be shared within and potentially outside the trusts and may be published e.g. in an academic journal. All personal data will be deleted/destroyed once the project has completed. If you have any questions about the survey, or would like to find out more about this project please email Alison White, Senior Project Manager at the Health Innovation Network on Alison.white20@nhs.net

The south London e-survey

Appendix two : Summary of the projects identified in the e-survey (workstream three)

Projects have been assigned an identification (ID) number within the table for the purpose of describing findings within this report. Project ID numbers are presented in square brackets [] alongside descriptions of the findings.

| Project ID | Organisation and services involved | Summary of project (aims and methods) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SWLSTG 2-3 Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and 2-3 adult services | Service user and staff experiences and perceptions of individual virtual video consultations carried out using the Attend Anywhere virtual consultation platform. Qualitative interviews with service users and staff. |

| 2 | SWLSTG Trust-wide | Patients’ feedback after Attend Anywhere consultation. Survey of patients. |

| 3 | SWLSTG Community mental health and psychological services across 8 sites | Feedback from people using outpatient mental health and psychological services on the experience of accessing care via digital systems. Survey of outpatients. |

| 4 | SWLSTG Sutton Mental Health Foundation | Sutton Mental Health Foundation telephone service evaluation: was the telephone support service (weekly phone calls) meeting support needs of service users and those receiving intentional peer support. Survey of service users. |

| 5 | SWLSTG Sutton Mental Health Foundation | Sutton Mental Health Foundation access to IT: what access do service users and volunteers have to the digital world and how can this be improved? Survey of service users. |

| 6 | SWLSTG Orchid Mental Health Emergency Service | Performance of the Orchid Mental Health Emergency Service (a service for patients of all ages with mental health problems who would otherwise have had to go to Accident and Emergency) since opening and impact on wider systems. Mixed methods – monitor performance against KPIs, service user experience, impact on local emergency departments and liaison psychiatry services. |

| 7 | SWLSTG CAMHS, Forensic and National Specialist services; Community; Acute and Urgent (Inpatient and Liaison services); Cognition and Mental Health Ageing service lines | Examine what impact changes in work practices (including shift to remote working) have had on experiences, wellbeing and productivity of psychiatrists and specialty and associate specialist (SAS) doctors Survey of consultants and SAS doctors. |

| 8 | SWLSTG Single-site, Fircroft Trust mental health and learning disabilities | The Fircroft Trust: supporting our clients during COVID-19 Unstructured telephone interviews. |

| 9 | SLaM Psychological Interventions Clinic for outpatients with Psychosis (PICuP) team | What proportion of service users have sufficient access to remote consultation technology in order to access remote psychological therapy? What are attitudes to PPE in return to face to face therapy? How to best provide therapy for people with psychosis in the context of covid-19. Survey of service users. |

| 10 | SLaM Promoting Recovery Teams and complex care services in Southwark (6 teams) | Gather data on the preferences service users have in relation to how they receive psychological therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey of service users. |

| 11 | SLaM National & Specialist CAMHS Obsessive Compulsive Disorder/Body Dismorphic Disorder team | A quality improvement project to improve staff and service user experience of remote assessments and treatment – a QI project. Mixed methods – qualitative and quantitative surveys during PDSA cycles. |

| 12 | SLaM Lewisham Memory Service, Croydon Memory Service, Southwark and Lambeth Memory Service | Evaluation of alternative neuropsychological assessments at SLaM memory services: what are patient and clinician experiences of alternative neuropsychological assessments? Are there any differences in satisfaction/ease of administration between 1) remote assessment, 2) socially distanced home assessment, 3) socially distanced clinic assessment? Survey of patients and staff. |

| 13 | SLaM Croydon Personality Disorder Service staff and service users | Working Remotely in the Sun Project: The experience of participating in our crisis and coping skills development group online – what works well online and what are the difficulties of working online? Qualitative. |

| 14 | SLaM Mental health community teams in Southwark, Lewisham, Lambeth and Croydon | Health Champions Study: A pilot hybrid effectiveness-implementation Randomised Controlled Trial of a volunteer Health Champion intervention to support people with severe mental illness to improve their physical health. Mixed methods. |

| 15 | Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership; Oxleas; SWLSTG Multiple sites, learning disability services | How are people with Learning Disabilities and their caregivers accessing ICT during the COVID-19 pandemic and what are the implications for their access to digital healthcare? Within the population of service users with LD and their caregivers are there sub- groups facing greater exclusion from ICT use? Implications during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Mixed methods. |

| 16 | National Multi-site / potentially international | Evaluating the experience of mental health care providers delivering psychological therapy online during a pandemic. Survey of providers of psychological therapies. |

| 17 | SLaM Main focus on Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Psychological Therapy Teams to date | What is the experience of virtual mental healthcare amongst patients and clinicians? (Mental healthcare includes mentalisation based therapy, group work, systemic therapy and psychodynamic therapy) Qualitative interviews. |

| 18 | SLaM All clinical services | Analysis of electronic health record data to assess the rates of remote consultation and psychiatric medication prescribing before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Quantitative analysis of routinely available data. |

| 19 | Oxleas All services | Assessment of how Oxleas NHS patients and service users feel about the shift from face to face to remote consultations. Survey of service users. |

| 20 | Oxleas Adult Learning Disability Team in Bexley, Bromley and Greenwich | Patient experience of remote consultations in the Oxleas Adult Learning Disability team. Survey of service users. |

| 21 | Oxleas Older people’s services | Patient experience of remote consultations in the older adults mental health service. Telephone survey of service users. |

| 22 | Oxleas Specialist children’s services in Bromley, Bexley and Greenwich | Staff experience of working during the COVID 19 pandemic. Survey of staff. |

| 23 | East London NHS Foundation Trust | Trust wide service evaluation of remote consultation platforms. Survey of clinical staff’s experiences and feedback. |

| 24 | East London NHS Foundation Trust | Arts therapy department survey of staff, service users and carer’s experience using online platforms to deliver arts psychotherapy. Survey of clinical staff, service users and carers. |

| 25 | North East London NHS Foundation Trust | Trust wide quality improvement project to evaluate roll out of video consultations in services, identify functional requirements, staff support and training needs. Survey of staff across the Trust. |

| 26 | Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust | Trust wide quality improvement project and service evaluation of staff and service users to inform service development and resource allocation. Surveys and qualitative interviews with service users and staff. |

| 27 | Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust | Service evaluation and quality improvement project of patient experience of remote consultations in community services. Survey of service users. |

| 28 | Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust | Quality improvement project to evaluate remote working in CAMHS, gender services, adult mental health services, education and training. Qualitative interviews and focus groups of staff, service users and carers, surveys and environmental impact assessments. |

| 29 | Place2Be | Ongoing service evaluation of parent counselling services taking place across England, Wales and Scotland. Interviews of service users. |

| 30 | Place2Be | Ongoing service evaluation of young people, parents, carers and teachers using the service in England and Scotland. Survey of service users. |

| 31 | YoungMinds | Service evaluation of young person’s remote access to CAMHs services. Survey of service users. |

| 32 | Mental Health Innovations | Strategy discussion to inform suture use of remote consultation in mental health services. Strategy discussion involving senior management staff and clinicians. |

Summary of the patient and staff surveys included in workstream 2

| Oxleas- patient survey | SWLSTG-1 – Patient survey | SLaM -patient, carer and staff | SWLSTG-2 Staff survey of consultant psychiatrists and SAS doctors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| purpose | To survey patient’s views on remote consultations | Evaluation of Attend Anywhere video consultation platform. Focus on financial and environmental benefit and overall satisfaction with the platform | Experience of virtual appointments/ meetings survey report (virtual means either by telephone or video) | To better understand how staff had adapted to the changes and the impact these had on productivity and wellbeing |

| population | Patients and service users | All users of the Attend Anywhere platform. General stats provided for all types of consultations within the time frame: total 65,878 | Staff, patients, and carers | consultant psychiatrists and SAS doctors |

| method | survey | Survey and some qual interviews | online survey (open for 8 weeks) | survey, different questions based on the type of service |

| delivery | by SMS or email using SmartSurvey, for older adults or people with LD this was done by telephone, timing of survey was considered in relation to other Patient Experience surveys being sent out (4 week gap between this survey and usual patient experience survey for a specific clinic) | Survey sent immediately post video consultation, this was embedded within the platform | link sent – unclear how (email, SMS?) had to be actioned by someone, not automatic. For phone consultations, someone had to ask the person the questions over the phone | survey designed on Survey Monkey |

| responses | 5,054 | 929 | 545 responses from staff (n=474), service users (n=47) and carers (n=24). | 80 |

| surveys sent | 35,933 | 7,589 | unknown | unknown but 160 consultants within the Trust |

| response rate | 14% | 12% | unknown | 50% |

| services targeted | Adult Mental Health (AMH), Adult Community Health (ACH), Children and Young People (CYP), Older Adults Mental Health (OPMH), Adult Learning Disability (ALD) | All services with Attend Anywhere uptake | unknown | Community setting and inpatient/liaison services |

| Patients/Service users | Staff | |

|---|---|---|

| Convenience | ||

| Reduction in travel (helpful when caring for children, disabilities) | Reduction in commuting | |

| No need to take time off work | Can invite more professionals to MDTs (e.g. GPs) | |

| Home setting/no waiting in reception with others | Consultants and SAS doctors: some said it reduced stress | |

| Comfort in home setting | Consultants and SAS doctors: Increased productivity – can complete work in the time normally used for commuting, meaning better work/life balance | |

| Less chance of missing appointments if forgotten about (can be called to start appointment or called and reminded to log into video call) | ||

| Inconvenience | ||

| Difficult when not computer literate | Home working environment lacking proper set-up (causing physical pains) | |

| Some platforms have a waiting room where patients were left waiting without being seen (Attend Anywhere) | Lack of boundaries between home and work life | |

| Might be difficult to involve family members in virtual MDTs | Virtual meetings seem longer, less urgency to finish on time | |

| Virtual meetings take more energy, feeling tired/drained after | ||

| Effect on symptoms | ||

| Reduction in anxiety about travel/leaving the house/faced with others in waiting room | Some staff felt patients were more open | |

| Easier to open up when not faced with someone | Some staff felt patients were more withdrawn | |

| For child services, some young children may not respond to video very well | ||

| Gaps when not meeting face-to-face | ||

| Physical examinations missed | Missing the informal interactions with team members where issues could be solved quickly without emails or meetings | |

| Body language is difficult to translate over video, and less over phone. Some felt they had to compensate for this which was a burden | Team check-ins are more formal | |

| Assessments with children is difficult when they don’t respond to video | Less down time or breaks in between meetings/consultations. | |

| Building rapport with people who have difficulties with social cues, or attention issues can be more challenging | ||

| Some interventions are not possible to do remotely | ||

| Short-term vs long term | ||

| Continuity of care during pandemic, safer | Continuity of professional responsibilities (consultants supporting their team) | |

| Might be open to continuing in the long-term for certain appointments | Some would like flexibility to continue to WFH at least a portion of the week | |

| Question about compensation if paying for own utilities and Wi-Fi | ||

| Choice | ||

| Patients would like to be given the option of face-to-face or virtual/remote consultations | SLaM survey: acceptance of virtual working is also higher when staff perceives they have a choice | |

| Uptake of virtual consultations is better when patients are given the choice | Staff would like more guidelines for staff on how and when to offer the different options (this is also stated in the improvements theme) | |

| Choice of telephone vs video, and if using a video platform, choice to keep the camera off | ||

| Improvements needed | ||

| More help to assist people who are not as tech savvy | Staff need better guides to offer patients, particularly for certain groups (older adults, forensic services, learning disability services) | |

| Access to better equipment and high speed broadband is needed, particularly in more deprived areas | Better IT support for staff, better guidance for when to offer virtual sessions | |

| Hospital Wi-Fi is not good enough for virtual video consultations | ||

| Changes to platforms might help, more features, better connectivity, sharing files | ||

| Privacy | ||

| Some patients feel staying at home is more private | Having the right location to minimise interruptions or ensure patient confidentiality is an issue for staff | |

| Depending on the home situation, patients might be less able to speak freely or disclose risk (e.g. domestic abuse) |

We’re here to help

Find out more about our work in mental health.