Insights By Profession

Select below to find out more about each role that was involved in the implementation process.

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

Both the Lead ePMA Pharmacist and the Project Support Officer had a pharmacy/technical background and were key to the success of the ePMA implementation project. They met with the ePMA system provider on a weekly basis to better understand the functions of the system being adopted, as well as creating a list of the most common drug prescription scenarios (the top 90) in order to pre-empt possible issues and arrive at appropriate technical solutions. This proved to be a labour-intensive process, which took the team approximately two years to complete. All decisions were ratified by the ePMA stakeholder group comprising clinicians, nurses and pharmacists.

As part of pre-implementation, a pilot was conducted. This gave the team valuable knowledge and understanding of the required changes to the clinical workflows. During this stage, the Pharmacy Team also forged strong working relations with the ICT Department, which proved very beneficial during implementation.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

For the implementation stage, the team expanded to six individuals with a mix of pharmacy and technical backgrounds.

The implementation process was undertaken in two phases. Initially, the ‘go-live’ was with the inpatient, followed by the outpatient flow. The discharge flow was separated from the inpatient flow because of the need for additional customisation. As a result, no set date for implementation was agreed for the discharge workflow, with it provisionally set to take place approximately one year after the implementation of the inpatient and outpatient flows.

The primary aim of the Pharmacy Team was supporting junior doctors in inpatient prescribing as much as possible and ensuring that their prescribing on the system was correct. They also followed up to make sure that nursing staff would not be faced with any issues in drug administration. To facilitate the training of doctors, the team ‘ring-fenced’ time outside of the everyday work of the doctors for which they would also be remunerated.

APPROACH

“We put together a list of the top 90 drugs and the problems about prescribing them…some simple and a whole variety of complex drugs…and created a whole list of scenarios that we took to the ePMA software provider in order to deliver solutions”

“What was asked for was a ‘ring-fenced’ time for the prescribers to do the transcribing and this was provided as paid over-time”

CHALLENGES

“There was resistance from the nursing staff but it was resistance to change (as opposed to resistance to ePMA)…There was also resistance from the Pharmacy Team”

“The pharmacists needed insight into how the nurses would work, how doctors would prescribe and what their workflow was… in essence they needed to be trained on all 3 workflows”

“The admissions ward didn’t ‘ring-fence’ doctor’s time for transcribing, so transcribing was late, and we were scrambling to get all the transcriptions complete.”

BENEFITS

“The benefits that are obvious are 100% legible prescriptions, more accurate recording, better data to do lots more”

Pharmacy ePMA Project Manager

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

Compared to the House Officers, who were more receptive to training, the senior doctors proved more difficult to train due to their availability. However, there was some level of resistance from all clinicians, the most common reason cited for resistance being time constraints.

The ePMA system also had limitations, the most important of which were its rigidity and the difficulty of introducing changes into it. For example, the system would not enable the printing of FP10 prescriptions for the dispensing of prescriptions outside of the hospital.

Those working for the ePMA system provider were mainly new to electronic prescribing or new to the UK market. This lack of knowledge was compounded by the fact that very few other UK Trusts had gone through the process of implementation in all clinical settings, meaning that few lessons could be use to inform ePMA implementation at Imperial.

KEY LESSONS

A key factor for success was ensuring the Pharmacy Team shared the same vision and end-goal, as this greatly improved team dynamics.

ICHT rolled out a combined Electronic Patient Record (EPR) system. If multiple vendor systems had been purchased for the EPR, Clinical Documentation and ePMA systems, significant time and resources would be spent on logging in and logging out and supporting training. This would have led to frustration amongst end-users and poor adoption.

Chief Pharmacist

Key Challenges & Lessons Learnt

BIOGRAPHY

Imperial’s Chief Pharmacist has been in post since 2014, having worked for ICHT for over 30 years in roles such as Site Lead Pharmacist for Charing Cross Hospital. This individual is an advocate for electronic-Prescribing, and whilst acknowledging the disturbances that might follow the introduction of an ePMA system, they emphasise that leadership within the Pharmacy Team can facilitate the changes to working practices that are needed to maximise the benefits of ePMA.

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

In the pre-implementation stage, the Pharmacy Team received extensive training by the Core Team. Without this training, ePMA implementation would have been less successful.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

Because of the strong relationship created between the Pharmacy Team and the ICT department, ICT staff were on hand to provide technical assistance and guidance to the Pharmacy Team when needed during implementation.

This was important, as the implementation of the ePMA system resulted in a large amount of extra work. Without this guidance, new starters and longer-term employees would have worked in different ways, leading to confusion among pharmacists. This guidance during implementation standardised working practices, preventing errors and delays in medicine administration.

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

Generally, the ePMA system provider supported the Pharmacy Team well, but they were often slow to respond when changes to the system were required.

Recruiting professional pharmacists skilled in the use of ePMA is challenging, but it can reduce training requirements.

KEY LESSONS

Eighteen months since implementation, there is an increasing number of care sets (lists of commonly prescribed medicines for specific areas) being built, due to their perceived value by staff. The expectation was that the number of these sets being build would drop off post-deployment, so this has led to an unanticipated additional ‘up-keep’ work.

Similarly, the implementation of ePMA has contributed to a notable increase in workload for the Pharmacy Team: it is estimated that approximately an extra half an hour is required per ward per day which due to system use.

Engagement with the online ePMA system provider user group proved very beneficial throughout the project and beyond. This is an active community where solutions are shared by others who have faced similar challenges.

APPROACH

“We have re-issued a 40-page manual for Pharmacy Staff on how to get the best use of the ePMA system. This supplements their training and facilitates standardisation of practices.”

CHALLENGES

“The ePMA system can sometimes be slow to respond. I like the system, and would not go back to the old one, but ePMA it is not without its issues.”

“It is heard to find people who are skilled in ePMA, pharmacists in particular…they’re just not out there.”

BENEFITS

“In terms of benefits realisation, mainly medicine saving costs… an evaluation is needed to establish that they are genuinely there.”

Chief Pharmacist

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

The Electronic Health Record (EHR) and the Clinical Documentation systems were introduced at the same time as electronic-prescribing. The Service (Clinical) Lead oversaw a small team at all three ICHT sites. Their primary role was to spread the understanding of how implementation of these three systems would take place.

This predominantly involved engagement with all staff, building support for the adoption of these systems. Efforts would continue until the scales tipped in favour for the implementation of the new systems.

This engagement included a presentation to each of the wards in which electronic-prescribing was going to be implemented. The presentation provided information not only about the system, but also about the changes to workflow needed to support its implementation.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

It was key to initiate implementation at a time when there was a majority in support for it. With minimal resistance, those at the ward undergoing implementation could work together and support one another to ensure that implementation was a success.

During this time, it was an asset to have the Service (Clinical) Lead and the Project Manager at the ward undertaking implementation. These two individuals could ‘hand-hold’ the ward through the implementation process, providing support to ward staff whenever needed.

The Service (Clinical) Lead and Project Manager at ICHT were viewed as ‘super users’ and it was because of this that they were able to support the wards so well during implementation.

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

The main challenge faced by the Service (Clinical) Lead was convincing the doctors of the benefits of the implementation of all the systems and securing ‘buy in’. Failure to do this can hinder adoption of the ePMA system, especially if the individuals resisting change are influential and able to encourage group resistance.

KEY LESSONS

There are a lot of risks associated with changes in workflow/ the introduction of new systems in Haematology, which made ePMA implementation in this area very difficult relative to other services.

Sufficient resources need to be dedicated to attain ‘buy-in’, as this is key to successful implementation.

Implementing these systems can be a very time-consuming task. However, if enough time is allocated for the planning stage, introducing all of them at once can be beneficial and not necessarily lead to information overload for staff.

Implementation of these systems is a process. It is therefore important to understand that at point of implementation, wards will likely become ‘paper-light’ as opposed to becoming immediately ‘paperless’.

APPROACH

“We waited to get enough ‘buy-in’ […] as soon as we perceived a shift from NO to YES, we went for it!”

“My whole time literally for a year was to get the ePMA system up and running within the division.”

“We also had the support of the floor-walkers, and they were probably the biggest help.”

CHALLENGES

“The biggest barrier we encountered was getting the ‘buy-in’ from the medical staff.”

“The Pharmacy Team needed to be aware of and trained in all three workflows: their own, the nurse’s and the doctor’s.”

Internal Cerner Lead

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

ICT Project Manager

Key Challenges & Lessons Learnt

BIOGRAPHY

The Imperial College Healthcare Trust (ICHT) ICT Project Manager oversaw the ePMA pilots in two clinical areas and the wider rollout across the entire Trust between mid-2015 and March 2016.

This individual coordinated the project utilising seven Project Leads and reported directly to the Deputy CIO. Currently this individual is a Senior Project Manager and has worked within ICHT’s ICT team for over five years, delivering several complex informatics-related projects.

LESSONS FROM PILOTS

Two areas were chosen to undertake the ePMA pilots:

- The Gynaecology ward and associated outpatient clinics

- The Medicine for the Elderly ward and associated falls clinic

These wards were chosen in-part due to:

- being clinically downstream

- the relatively low number of patients that move from them to other clinical areas.

The pilots were supported for approximately six months and had clearly defined exit criteria.

The pilots at ICHT actively identified as many problems and issues as possible. This allowed for the development of preparation packs for the subsequent rollout, where lessons from the pilots were used to reduce the risk of reoccurrence. For example, in terms of infrastructure, the pilots enable ICHT to better understand the number of drug rounds and the number of locums that would be needed. Furthermore, identifying these problems gave valuable insight when planning for areas with more complex requirements.

Another key lesson from the pilots centred around attempting to minimise the amount of customisation/bespoke builds for individual wards. This approach was justified based on significant amounts of time being spent during the pilots replicating existing proformas for a specific clinic, which were subsequently not used by those staff (who opted instead to use the standard functionality).

Some drugs and specialised scoring charts encompassed a significant level of complexity. As a result, an expectation was set that implementation, at least initially, would be ‘paper-light’ as opposed to ‘paper-free’. Solutions for exception cases would also be found later, with the solution integrated post-implementation.

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

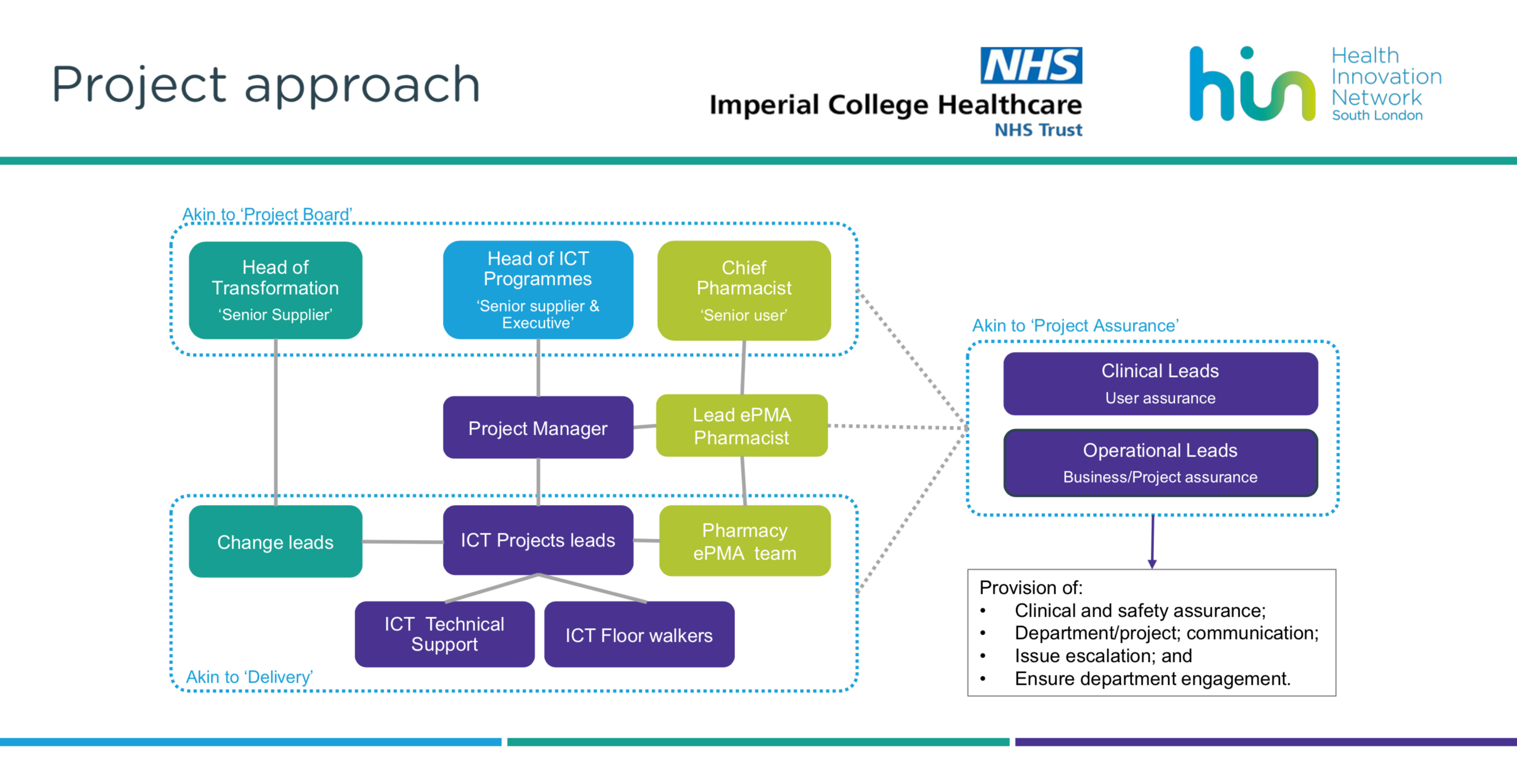

Effective relationship dynamics

The approach to implementation was a joint effort between Imperial’s Change Team, ICT Project Team and Pharmacy Team.

The use of floorwalkers

The use of IT floorwalkers had proved highly effective during Imperial’s Patient Administration System (PAS) rollout and therefore the approach was utilised again, with 80 floorwalkers maintained throughout the project.

The floorwalkers were recruited through an agency and were subject to a significant ‘churn rate’. It was observed that those who made the most of the training available to them were the most successful.

The floorwalkers were based within the clinical areas and delivered bedside training and troubleshooting assistance. Each floorwalker was assigned an ICT Project Lead to whom they escalated issues and requests that were beyond their remit.

Following the main activities associated with ePMA rollout, the number of floorwalkers was approximately halved, with a conscious attempt made to only retain the best floorwalkers. This approach proved to be an effective recruitment tool for ICHT, where a significant percentage of floorwalkers retained were offered permanent admin and clerical positions within clinical services, with some becoming project support officers and eventually project managers within ICT.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

The ICT team developed an algorithm to determine the number of computers required in areas/wards based on the completion of the preparation packs. This enabled the ICT team to track utilisation of equipment to prevent ‘gaming’ around hardware supply, and consequently allowed additional systems to be held as contingency.

KEY LESSONS

“Providing extra training for junior clinical staff proved to be the catalyst for success, as they would, in effect, train the senior clinicians in the use of the system.”

“Having ‘buy-in’ from the nurses created the backbone for successful adoption. This was because once the nurses administered medicines using the ePMA system, the doctors would have to use it. If they failed to do so, medicines would not be administered and doctors (but not nurses) would be to blame.”

CHALLENGES

“The hardest part of the ePMA implementation were chart transcriptions. This required precision and took a lot of time.”

“The most common issues during stabilisation were around smart cards and system access”

BENEFITS

“With an ePMA system, those administering medicines do not have to worry about the frustration of not being able to read the handwriting on a prescription required to be dispensed.”

WHAT THEY WOULD DO DIFFERENTLY

“Dedicating more time for each tranche and having more spacing between tranches (to avoid overlaps) would have been highly beneficial.”

ICT Project Manager

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

CHALLENGES ENCOUNTERED

Culture

The implementation of the ePMA system required a change in culture, as clinical staff had to take responsibility for system use. From a governance perspective, ICT could not take on board that responsibility and it had to rest with the clinical teams on the wards. If clinical teams had not been committed to the new system and the new culture, then ePMA would not have been adopted.

Engagement

A lot of effort was required to attain senior clinician ‘buy in’. This was viewed as a key component of engagement, as it these influential individuals could promote the ePMA system it among colleagues and encourage them to attend the training sessions.

“ICT could not take responsibility for achieving 95% training compliance, and this needed to be owned by the services themselves. They needed to make use of as much training as they could and sign off that they were happy with the training levels. A key component to that was having senior buy in to ensure that areas couldn’t ‘pass the buck’.”

Resistance

During ICHT’s implementation there was anecdotal evidence that some clinical staff expressed their resistance to change by effectively telling others not to enter data into the system and to continue using paper. This led to dual drug charts and confusion for nurses around what drugs to administer to patients.

At ICHT clinicians could easily disengage and avoid training if they wanted and then subsequently blame a lack of training for their limited understanding and system usage.

A training structure which would minimise this aspect of resistance was required. Consequently, efforts were made to design a training schedule that supported clinicians and provided valuable incentives to increase training uptake.

“People that don’t engage often say – ‘I’m not doing it because I wasn’t trained’ – which may be a cop-out in some cases as it is really easy to avoid getting trained if you don’t want to.”

Planning

The training structure and the enforcement of training was an important element of the planning stage.

Large issues centred around the inability to afford staff time away from their everyday work to undertake training. At ICHT, staff sometimes would not be released to undertake training. This was viewed as either a lack of organisation or an impossible task.

Training

ICHT realised that classroom approaches were not the most appropriate or engaging training method.

Different services approached training in different ways, with varying degrees of success. The most effective training was that provided by ICT: a bespoke in-situ training approach to clinicians, which leveraged a strong support model, using approximately 80 floor walkers.

Infrastructure

The limited physical size of rooms, controlled side-rooms and the need to abide to infection prevention regulations proved to be an issue. This, along with different equipment requests from different staff members (in terms of drug carts, power outlet numbers ….) meant that infrastructure could not be standardised.

Other Issues

The Change Team was required throughout the entire ePMA implementation process, including planning, deployment and post-implementation.

With tranche roll-out overlapping, their resources were frequently stretched. More time and spacing between tranches would have eased this pressure.

The hardest part of the ePMA implementation was the chart transcriptions. This required precision and utilised a lot of time.

The most common issues during stabilisation were around smart cards and system access.

In terms of implementation, the most difficult wards were Renal and Haematology. This was due to complicated drug processes, and an existing rigid culture.

ICT Project Lead A&E

Key Challenges & Lessons Learnt

BIOGRAPHY

Imperial College Healthcare Trust (ICHT) ePMA roll-out was organised into tranches corresponding to hospital sites across the Trust. Responsibilities for the tranches or the areas/wards within the hospital sites were divided amongst seven Project Leads reporting to the overall ICT Project Manager. The Project Lead interviewed was responsible for A&E and the Acute Ward (step down ward) and now acts as a Project Manager within ICHT’s ICT team.

CHALLENGES

“The most challenging aspect of ePMA implementation was transcribing medication charts, which the Project Leads had to plan and time well.”

“Even with a hardware needs assessment having been conducted during planning, in A&E clinical staff were initially queuing to use the computers. As a result, additional computers were required from the contingency stock.”

USEFUL LEARNING

“In the first few weeks (post-implementation) the complaints were mostly around computers being slow […] things that could be resolved quickly. Queries containing real issues and barriers were not received until two to three weeks down the line”

BENEFITS

“ePMA allows clinicians to prescribe very quickly using care sets (catalogues of medications you are most likely to prescribe within a particular clinical area) designed in collaboration with clinical staff.”

ICT Project Lead – A&E

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

ICHT decided to introduce a Clinical Documentation system at the same time as ePMA implementation across the entire Trust. In addition, ICHT put a pause on any other change projects that could potentially impact upon the successful rollout and adoption of these two solutions. Due to concerns and worries related to simultaneous roll-out of both systems on the same day, the Clinical Documentation system roll-out was planned for the week prior to ePMA roll out at each ward.

The approach to design and creation of care sets was a collaborative one, with the Service (Clinical) Leads and Pharmacists being involved. Care sets (i.e. catalogues of medications that are often prescribed in a clinical area) were useful because they made the process of prescribing common medications very quick and efficient. They were a necessary step prior to ePMA implementation in A&E. Care sets also provided the added benefit of easing the training process for clinicians during the pre-implementation phase. They could be used to explain the functionalities, uses and benefits of the system.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

Feedback and escalation mechanisms were adopted during implementation. At ICHT, queries from staff about ePMA could be made through the IT floorwalkers, the Change Team and the IT Helpdesk.

These mechanisms worked in various ways:

- Daily catch-ups allowed issues to be discussed and escalated as required.

- The IT Helpdesk established a dedicated ePMA queue which was handled by the Pharmacy Team.

- On the ground, clinical staff could raise issues encountered with their designated floorwalker, who would escalate to the Project Lead as required, who would then come in person to address the issue.

To pre-empt issues arising, floorwalkers at A&E and the Acute Ward would take note of the clinical staff working in their area and send updates regarding their understanding and additional training requirements. In addition to this, the attitude of clinical staff towards ePMA (colour coded: positive to negative) was recorded to target those that required individual encouragement by the Project Lead. This exercise highlighted that approximately 10% of staff required additional support beyond their initial training.

The stabilisation phase lasted approximately one-month post implementation, during which the escalation mechanisms remained in place. However, the floorwalker numbers immediately post-implementation were purposely reduced, with the IT Project Team completely disengaged after 2 months. It was felt that the presence of floorwalkers and support from the IT Project Team could have been longer to allow more time and less pressure to transfer to business as usual.

WHAT THEY WOULD DO DIFFERENTLY

“I would have spent more time on communication and awareness in advance of the rollout. Our means of communication was the intranet, which is not used by everyone. We generally spoke to more senior staff, and when it got to showtime, the people on the floor didn’t know much about it (they were aware of it but didn’t have enough details). We were counting on the Service (Clinical) Leads and seniors to cascade this information but it wasn’t happening. We could have used the floorwalkers to raise awareness prior to the rollout, which would have reduced resistance.”

ICT Project Lead – A&E

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

CHALLENGES ENCOUTERED

Planning

The most challenging aspect of ePMA implementation was transcribing medication charts, which the Project Leads had to plan and time well.

Medication coding was a further challenge. Medications were initially coded by their pharmacological name, not the branded name, which created frustration amongst the clinicians when searching for medicines, who routinely search brands. However, with this identified early in the planning stage, care sets were adapted to alleviate this concern and medications were coded by their branded name.

Optimisation

In terms of the system optimisation, the challenge of workflow integration was always present within all clinical areas. For example, patients would be classified as an ‘emergency encounter’ when admitted in A&E using an EPR, but when moved to a different ward, they would be reclassified to an ‘inpatient encounter’. As the encounters are specific, the medications would change in relation to the workflow.

Resistance

Attaining ‘buy-in’ of clinical staff (doctors, nurses and pharmacists) who expressed resistance was a key challenge for the project leads. Clinicians agreed with the long-term benefits of ePMA but the immediate ‘doing’ was the challenge. During pre-implementation, the concerns from clinical staff were largely centred around the effects upon patient experience. The main reasons of concern were:

- ePMA reduced face-to-face time with patients

- ePMA requires additional work.

- Lack of computer literacy among clinical staff

Other concerns raised were around very specific things, which could have been de-escalated by listening, clarifying and talking through solutions.

Infrastructure and Equipment

At the planning stage, a hardware ‘needs assessment’ was undertaken. However, at time of roll-out, A&E clinical staff were queuing to use computers. As a result, additional computers were required from the contingency stock.

A ‘Tap and Go’ functionality was explored for adoption. This would have allowed multiple users to input data into a patient record without having to log in and out, but this was not taken up.

Adopting this functionality may have had a positive impact on implementation.

KEY LESSONS

Correctly estimating the amount of time required to transcribe the medication charts and build the care sets is imperative. At ICHT, it took a significant amount of time to design and test medication care sets, particularly for A&E.

The roll-out of the Clinical Documentation system before the roll-out of ePMA proved a key factor in the success of the implementation project, as it avoided information overload of clinical staff at any one time.

In addition, as the Clinical Documentation and ePMA systems in tandem, once the Clinical Documentation system had been implemented, clinical staff were asking for ePMA. Adopting both reduced the need to duplicate data entry.

Training can be more effective if care plans can be shown to the clinicians during the training period. By doing so, training can be quicker and easier to understand.

Often, the team/clinicians that see a trauma patient in A&E will be the same clinicians that see the patient later in their journey (i.e. orthopedic surgeons). Capturing the information correctly and comprehensively early on benefits the clinicians later, so this helps spread enthusiasm about the adoption of these systems. This aspect of planning enabled certain clinicians to become the ePMA system’s biggest advocates.

Having an engaged Pharmacist Lead that allowed the Project Team to work closely with the Pharmacy Team was key to overcoming resistance among pharmacists.

Clinicians who are stubbornly resistant to the adoption of the ePMA system must be listened to.

Quite often they are worried about something very specific which can be overcome, and when their concern is addressed their level of resistance decreases.Ensuring the availability of post-implementation support is imperative to ensure a smooth transition to Business as Usual (BAU).

The project team at ICHT was ready to receive large numbers of queries at ‘go live’. However, this wasn’t the case. In the first few weeks, the complaints that did come in were mostly around computers being slow etc. – things that could be resolved very quickly. Most queries were not received until two or three weeks after the roll-out. Time is required for users to identify real issues and barriers.

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

The primary focus prior to pre-implementation was to provide the floorwalkers with training and help them familiarise with training materials. During this time, they were given time to practice and learn most (if not all) of the functionalities and advice on how to best approach consultants and work within clinical areas.

Training at the pre-implementation stage was very important. Of note, the time required for training varied depending on what type of ePMA functionality was being shown, how comfortable the clinician was with the functionality and how much he/she wanted the floorwalker to cover.

More than 35-40 minutes were needed to cover the ePMA hospital-wide discharge functionality to nurses. However, if only certain sections were being shown, only 20 minutes were required.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

Floor walkers were required to cover all shifts (including the night shift): 9am-5pm, 3pm-8pm, 8pm-12am. Additionally, on the first day of the rollout in each area, they would be present from approximately 7am.

As implementation continued, support was still required from the floor-walkers. Given that certain people learnt how to use the system more rapidly than others, it was important that the floorwalkers were available to provide ongoing support beyond the initial training effort. It was noted that consultants did not need as much support as nurses did.

KEY LESSONS

After providing initial support to a staff member, floorwalkers should follow up on this individual to make sure they consolidate their understanding of the system. This follow-up element is greatly appreciated by the staff and helps to build rapport between floorwalkers and clinicians (especially consultants).

Setting up ‘dummy’ patients on the systems can be very useful, as it allows to go through different clinical scenarios during the training sessions.

Support to consultants and nurses is most efficient when provided by a team of floorwalkers who are not only knowledgeable at the individual level but also work well together as a team.

Consultants and nursing staff need extra support during the ‘go-live’, so it is imperative that the floorwalkers are around. Knowing that floorwalkers are always available to support them provides invaluable reassurance.

Although continuous support is essential, it is important not to hover around the prescribing staff: as a floorwalker, it is important to know when someone requires support and when they not.

APPROACH

“When doing the training, we tried to get nurses into groups of 3 or 4 so that they could work as a team.”

“We worked as a team […] I could ask person A or person B for help when there was something that I did not know how to do […] team work helps everyone widen their knowledge base by picking up skills from one another.”

“We had a green lanyard with floor-walker (or ePMA) upon it so that staff would know to approach us.”

“You may need to repeat yourself (to consultant staff especially) a million times. It doesn’t matter so long as in the end-user is happy and confident.”

CHALLENGES

“The biggest issue was trying to get everyone to attend the training sessions, […] so getting the timing right is really important […] you always must work around their availability, which can be difficult at times.”

“You are expected to know everything (about the ePMA system)”

“It’s sometimes difficult to get the consultants on board, maybe because of their limited availability […] Others are slightly conservative and want to continue doing things the way they always have. Some are absolutely appreciative of the technology and the development, so they are on board. You will get a variety.”

“It’s slightly different once you go live. Training is one thing…but once you go live… that is when panic mode sets in.”

ICT Floorwalker

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

Lead Nurse – ED

BIOGRAPHY

The individual interviewed was the Lead Nurse during the implementation of electronic-prescribing in 2014 and was subsequently involved in the optimisation journey (which started initially in the Emergency Department), later becoming the Chief Nursing Information Officer (CNIO).

APPROACH

“Both myself and my CCIO undertook some clinical work, prescribing on the system and administering drugs. This means that we knew where the pitfalls were.

CHALLENGES

“It is important to realise that if you were a bad nurse or doctor before the implementation of the ePMA system, you will still be a bad clinician after it is adopted… the system will simply allow you to be a bad clinician electronically. It [the system] will nudge you in the right direction, but it won’t replace clinical training and acumen.”

KEY LESSONS

“Identifying and using local champions to advocate electronic-prescribing at pilot sites and encouraging healthy competition between wards proved to be an effective way to drive improvement, promote behavioural change and facilitate the adoption of the new system.”

BENEFITS

“We’ve recently analysed the time of medicine administration for Parkinson’s (time of administration versus scheduled time) to see if we’re giving it late […] it turns out we’re actually really good at this!”

“We get criticised all of the time for our pain relief: do we give enough?… I don’t know! But, what I can tell you NOW is exactly how much we do give and put that against the pain score that we’ve recorded. This shows what a patient’s pain score and analgesia dose were within 60 minutes of each other… I can now see whether we acted on the pain score or did something different.”

Lead Nurse – ED

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

In the old system, independent prescribers could prescribed medication for those who were not independent prescribers by writing Patient Group Direction (PGD) on the front of a prescription (on an allotted space on the front of the drug chart). Whit the new ePMA system, a separate code attached to the drug was necessary for PGD-qualified staff to access a subset of the formulary. This required extensive testing before implementation both for auditing purposes and to ensure patient safety.

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

Some of the key barriers encountered during implementation were due to the limitations of the ePMA system. Firstly, the ePMA system does not provide a mapping table from the front end to the back end. There are many tables present within the system (approximately 1000) but the manufacturer cannot tell you whether a particular field of a certain table relates to the front-end or the back-end.

Another limitation of the system was that whenever the back-office team creates a new field or undertakes some level of customisation, the system’s front-to-back end stops working. It is the responsibility of the trust to keep this up-to-date to ensure it keeps functioning. Therefore, ongoing maintenance is key to ensure that the system runs smoothly.

KEY LESSONS

Testing is essential, but implementation success does not depend on the amount of testing that is undertaken. All drugs incorporated into the formulary are prescribed in the same way, making it unnecessary to test how the prescription process works for every single one of them. The most important element is to build the formulary carefully, making sure that all the options included are correct and therefore eliminating the possibility of inadvertent misprescribing. To ensure this, ICHT spent a significant amount of time checking and then counter-checking that a prescription electronically written was the right prescription.

Identifying and using local champions to advocate electronic-prescribing at pilot sites and encouraging healthy competition between wards proved to be an effective way to drive improvement, promote behavioural change and facilitate the adoption of the new system.

The tranche strategy was very successful. However, the Emergency Department required an immense amount of resources to go live across 3 sites at same time (even after implementing the ePMA system in services downstream of the Emergency Department first).

Training of clinicians was far more effective if delivered by fellow clinicians with the presence of an ICT trainer. Training provided by ICT trainers only proved to be less effective, resulting in significantly more errors by medical staff.

The training programme does not need to be excessively long in order to be effective. At ICHT, training was restricted to the week before the ‘go-live’ to enable the learnings to be as fresh as possible in the minds of the clinicians. Although this can be an advantage, it is important to understand that this does not mean that support after ‘go-live’ will not be required.

Data collected from electronic-prescribing can be extremely valuable. These data can reveal clinician behaviour that previously went unnoticed and be used as evidence to encourage behavioural change and facilitate standardisation of clinical practice. However, this data analysis needs to be undertaken by someone familiar with the clinical workflows so that outliers can be identified and corrected. This will reduce bias in the analyses that are undertaken.

Data can also be used to understand and reduce mortality rates in certain areas. For example, in the case of sepsis, documentation of the time of drug administration in relation to the time of admission can help identify best practice and help drive life-saving improvements forward.

ePMA PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

Prior to implementation, the Change Team conducted multiple stakeholder meetings to understand various issues including clinical workflows and reliance on existing tertiary systems. It was imperative that the Change Team engaged with all the relevant stakeholders from the beginning of the process to attain their ‘buy-in’.

It was the role of the Project Manager to meet with key individuals, to obtain the names of the relevant stakeholders and assist in the completion of the preparation packs for each clinical area. This was used to draw quick conclusions about whether their requirements and processes were standard or more complex in nature (e.g tertiary systems) reporting back necessary requirements.

There were specific timeframes for producing this documentation, collecting information and attaining sign-off, which were supported by a very good escalation process. When collecting this documentation was difficult, more senior groups could be called upon to assist.

The initial engagement used by the Project Lead was to identify the right stakeholders through the Clinical Lead and Business Lead and hold ‘kick-off’ meetings with all those identified in one room to show exactly what they were trying to achieve. This proved to be invaluable and has been adopted as a key approach going forward with other projects that ICHT are involved with.

Through this process they identified those who were very positive towards the use of electronic-prescribing. These individuals were then encouraged to ‘champion’ the system and support those who were a little more nervous about changing their working practices. The Change Team would also approach those perceived to be nervous, by sitting with them to understand their concerns and reassure them.

The Change Team placed posters in the wards that were soon to ‘go-live’. These contained key information on the new processes and workflows. They were easy to read and outlined the starting points, stops and continuations so that prescribers could see exactly how they should be working on the ‘go-live’ day.

As these posters and their guidance were set primarily on the viewpoint of the prescribers (the doctors and nurses) and their interactions with patients, it was important that the Change Team included individuals with a clinical background.

ePMA IMPLEMENTATION

The implementation of the ePMA was a very dynamic project and took a ‘learning by doing’ approach. Efforts were made to use lessons from implementation at one site to inform future actions at other sites, while at the same time endeavouring to maintain a level of consistency.

APPROACH

“It’s very difficult to speak to everybody […] It can therefore be extremely useful to identify key individuals who can communicate the instructions from the Change Team to those who cannot be easily reached.”

“Within the Change Team, it is important to have people with different backgrounds who can understand the issues from different angles. However, it is important to try not to let Change Team members get too specialised in one specific area.”

“Change Teams members should share learning amongst themselves to add maximum value to the project and improve the way they train clinicians and Trust staff to use the system.”

KEY LESSONS

“Clinician-led training is best. It facilitates an understanding of the clinical workflow changes that the system introduces, rather than focusing exclusively on ‘clicking’ through”.

CHALLENGES

“Building commitment to change is always a challenge. We probably could have looked at it more from an end-user perspective rather than from a system viewpoint.”

“Older, more established clinicians tend to be more resistant to change, as they have been doing things in a certain way for a very long period of time. Introducing lots of changes and standardising practice in this group can sometimes be very difficult.”

BENEFITS

“A key benefit of this project was getting teams from across the Trust to talk with one another, which would not ordinarily happen. This greatly contributed to the spread of knowledge.”

Change Team Lead

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

Workflows proved to be more complex in areas that used a tertiary system. Using a generic solution, which would be feasible in other areas, was not always possible in these areas.

It can be difficult to build specialty-specific content for these areas within the timeframes of the project. It is also not possible to eradicate the tertiary systems, because they are reporting tools. It is therefore important to keep in mind that the workflows for these areas are more complex and a lot more work is required to facilitate the adoption and implementation ePMA.

The rollout of ePMA at ICHT was very quick. As a result, the Change Team were occasionally not able to communicate with the clinicians as effectively as they would have wanted. This meant the clinicians were sometimes resistant to sign off on the implementation programme and further meetings were required to attain sufficient buy-in.

KEY LESSONS

Consulting with all relevant stakeholders is important, as it makes it easier to maximise mutual understanding of the system.

‘Setting’ constraints make the process of implementing ePMA very difficult: moving through a hospital, especially when there are many specialities spread across multiple sites, is time-consuming and challenging.

Training must include not only information on the new clinical workflows to be adopted but also on the technical details about how to best use the system.

The significant amount of time required to specialise/customise the ePMA system for tertiary systems must be born in mind. It can be easy to ‘go-live’ with a generic solution, but more time is required in planning and maintenance when customisation is required.

The ePMA system workflows incorporating tertiary systems are more complex than the standard systems. There can be significant risk to patient safety (related to the location of the patient record) if multiple systems (standard and tertiary) are being used. As a result, this must be handled very carefully, incorporating and planning for the necessary processes that need to take place.

APPROACH

“It was essential to conduct two pilots because this allowed us to test the system with different patient cohorts, clinicians, working styles, clinical workflows… and even writing styles.”

“(For the pilots) we chose two areas which were going to have the ability to cope if there were problems and had relatively few interactions with other services. At the same , we made sure that these two areas would expose the Project Leads to a variety of patients and clinicians.”

“We wanted training to be engaging and clinically relevant rather than being focused on software-specific processes. Simply ‘clicking through’ engages no part of the brain.”

CHALLENGES

“From the physician perspective, the biggest change was to the discharge prescribing.”

“It is difficult to get people to engage when they have other priorities.”

“It’s very difficult to separate out the technical aspects (i.e.how you do things on an electronic system) from the aspects of decision making and prescribing. Partly because they are the same thing.”

“Changing to electronic prescribing is high-risk. We hand them the “tools and the keys” to do prescribing on the electronic system from day one.”

“Floorwalkers were initially too reactive, waiting to be approached. However, their role proved to be much more useful when they actively engaged with the teams to tell them what they were doing well (or wrong) and suggest improvements. ”

Consultant Doctor

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

ePMA (pilots) PRE-IMPLEMENTATION

In planning for the pilots, it was agreed that the electronic Clinical Documentation system would be deployed a few weeks prior to ePMA. This allowed the team to become familiar with the system ‘as a whole’.

The Consultant Lead for the pilots took a very active role in the preparation stage, supporting the transcription training of junior doctors, who received a 3-day package of training focused on clinical engagement.

KEY LESSONS

Training is essential and ICHT stress the importance of pro-active training delivered in an engaging way (rather than passive, repetitive training regimes that simply allow trainers to ‘tick the boxes’).

A move from paper to electronic prescribing requires significant planning effort and special attention should be placed on effectively managing the ‘go-live’ changeover day.

BARRIERS ENCOUNTERED

The ePMA used at ICHT is based around an American philosophy. In the United States, patients have different healthcare providers and there is not a single central record of their medicines. This presents an issue when applied to the UK model as the system’s functionality does not align ideally with the workflow.

A clear structure of the pilots was not provided. Those involved in the pilots would have preferred to be better informed about how their feedback was being taken into account.

There was a lack of clarity and transparency of the actions undertaken by people. It would have been useful to share data on ePMA system use or common mistakes.

Drop-in sessions were organised to provide support and follow-on help for new doctors after initial training, but attendance was very low. At the first drop-in session at ICHT, only 2 out of the 400 new doctors attended. This was remedied through better promotional activities, but it was still found that the doctors attending the drop-in sessions were the ones interested in furthering their knowledge and not the one who were making mistakes and needed these sessions the most.

BENEFITS

“A huge pro is that you can access the records everywhere; at home, at the office […] if someone calls me up, I can actually see what they’re talking about, and we don’t need to hunt for notes for twenty minutes.”

“The discharge prescription process shows you every prescription, every document, and any other previous prescriptions. This is helpful because you would know that if a patient came in on a beta blocker at ‘this’ dose and we prescribed a beta blocker at ‘that’ dose, you could then ensure that they would be put back on to their normal dose post discharge (as this was only temporary change during the admission).”

Consultant Geriatrician

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

INGREDIENTS FOR SUCCESS

Floorwalkers

Following the successful use of ICT floorwalkers to support digital transformation work elsewhere in England (Bath being cited as a specific success story) ICHT adopted a similar approach. In 2014, 250 floorwalkers were recruited through Brook Street agency to undertake a big bang Patient Administration System (PAS) rollout.

It was felt that if a tranche approach was taken over the subsequent six months, the ePMA implementation would require four to five times fewer floorwalkers than would be needed for a ‘big bang’ approach. This would also lead to the recruitment of higher calibre individuals by offering longer-term contracts.

Approximately 80 floor walkers were in post for eight months over the duration of the project. They were recruited a month prior to the rollout, undertook training and were kept on for an additional month at the end. They were generally made up of graduates but also of those with several years of experience.

The intention was to keep on as many of the floorwalkers as possible after the completion of the project, knowing that there would be a constant stream of other projects. However, ePMA required a longer period of stabilisation before additional functionality could be rolled out and therefore a large proportion of the floorwalkers were let go.

Finally, it is important to note that the floorwalkers were the most significant cost in rolling out the product.

Senior ‘Buy-in’

The Chief Executive, Nursing Director, Chief Pharmacist and Medical Director were all very enthusiastic about the implementation of the ePMA system. This meant that there was access to the finances required, which included the costs of both implementation and the ‘go-live’.

Clinical Engagement

Clinical engagement at the senior level was a key for the success of the project. Having a Clinical Project Lead for each tranche, scheduling regular meetings and being responsive to the needs of the sites were also instrumental in ensuring a smooth implementation. For example, this enabled a late decision to change the Hammersmith position in the roll-out following feedback from clinical staff around patient flow between sites.

Other Factors

A major factor for the smooth out-run of the project was the range of people involved. Another factor contributing to the success of ePMA was the presence of a robust incident tracker and issue escalation mechanism. The wide range of people involved and the ‘whole organisation’ approach greatly contributed to the smooth out-run of the project as well.

The preparation packs were also very useful, as they provided a vehicle to engage with those on the front line.

Infrastructure and Equipment

ICHT benefitted from their approach of buying hardware only for the first two tranches and monitoring its utilisation once put into service. This reduced the cost of hardware for the final tranche as equipment not being used was re-allocated. Furthermore, involving the clinical areas in the selection process for trolleys and equipment proved to be great publicity for the programme.

APPROACH

“Deciding the safest way of approaching the implementation was key: the senior team had to weigh up the risks of taking a big bang (i.e. very rapid) versus a more gradual approach, which would require having a hybrid record.”

CHALLENGES

“At lot more was needed around infrastructure and hardware than originally anticipated. In addition, some of the equipment was not suitable for certain areas and maintaining a large number of computers on trolleys proved to be an issue, requiring a premature equipment replacement.”

BENEFITS

“An additional benefit to undertaking this work was that it enabled Imperial to attract high calibre professionals into the Trust”

WHAT THEY WOULD DO DIFFERENTLY

“I would put more focus on what equipment would be needed”

Head of ICT Programmes

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

CHALLENGES

Choosing the Deployment Strategy

The key challenge around ePMA was determining how best to support end-users in a cost-effective way right after the ‘go-live’. The Senior Team had to weigh up the risks of taking a ‘big bang’ approach versus undertaking a more gradual approach, which would require having a hybrid record. In the end, a tranche approach was taken to minimise the amount of transcribing required when patients moved between areas which did or did not have ePMA in place.

Outpatients

The system was not widely adopted in outpatients. One reason for this was that patients needed to keep a physical ‘token’ to make it easier for them to collect their correct prescriptions at Lloyds Pharmacies.

Connection to Pharmacy

There was no linking element beyond basic patient details between the Pharmacy System and the ePMA system, which prevented the pharmacists from realising the full benefits of ePMA implementation. This is currently being addressed at ICHT.

Infrastructure & Equipment

One of the more challenging aspects throughout implementation was around infrastructure and equipment. Many more computers and trolleys were needed than originally anticipated.

The equipment specifications chosen during the planning stage also turned out not to be adequate for certain areas. For example, the initial plan was to use large screen laptops on trolleys, but for large wards, rounds required bigger screens and longer lasting batteries. The specification was therefore changed to include powered carts, which came at a considerable additional cost. Furthermore, maintaining many computers on trolleys has also proven to be an issue since the rollout, and has had the unintended consequence of requiring a premature equipment refreshment.

ICT Technical Support Manager

BIOGRAPHY

This individual led the Technical Support Team for Imperial College Healthcare Trust (ICHT), which included teams at each of the main sites (Hammersmith, St. Mary’s and Charring Cross). This team managed all the end-point devices (e.g. PCs, laptops, printers) and provided hardware and second-line support for the implementation of ePMA.

During ePMA implementation the primary, role of the Technical Support Team was to supply ‘PCs on wheels’ and carts as per the requirements stated in the preparation packs completed by each clinical area.

CHALLENGES

“The ePMA user interface is not made for tablets, so it does not adjust and does not present in a user-friendly manner”

“At ‘go-live’ no significant issues regarding laptops were highlighted. However, faltering batteries became an issue as time went by.”

CHALLENGES ENCOUNTERED

Limited choice of hardware

In terms of choice, the marketplace presented with very few options.

Logistical concerns

Many of the concerns that arose during implementation were basic in nature. For example, the Technical Support Team had to make sure that the cart cables were of the right length and that there were not any powering issues (e.g. adequate number of power sockets, long lasting batteries).

Old hardware still in operation

At time of ‘go-live’, older devices were in still in circulation, some of which were between five and ten years old. This caused issues, as some devices were too “slow”.

Laptops

At ‘go-live’ no significant issues regarding laptops were highlighted. However, faltering batteries became an issue as time went by.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Screen size

The largest laptop screen size possible (17 inches)was chosen for use on the carts. Larger screens were preferred because the ePMA system user interface can be very ‘busy’ and users would have likely become frustrated if required to constantly scroll up, down, left and right on smaller screens.

PC monitors of 23-24 inches were preferable to laptops but required expensive powered carts.

More time during implementation

The Technical Support Team would have benefited from extra time during implementation. Delays in equipment purchasing and delivery by suppliers meant that the team were frequently under pressure and needed to work beyond their normal hours and at weekends.

Power outlet assessment

In a few cases, the Technical Support Team found that because of having an ‘old estate’ there were not enough power outlets in the clinical areas to support the PCs. It would have been useful to undertake a pre-implementation assessment of the power outlets.

The benefits of PCs

The Technical Support Team identified certain limitations with the use of laptops. Therefore, they explicitly recommend powered PCs to be the hardware of choice due to improved:

- Longevity

- Robustness

- Security

- User experience

- Ease of management by the Technical Support Team

- and lower risk of failure

Allocated funding

The Technical Support Team could have supported users more effectively if during the planning stages funding had been allocated for refreshing hardware, procuring faster hard-drives, new batteries and additional devices.

Technical Support involvement in initial requirements assessment

The Technical Support Lead believed that the Technical Support Team should have been involved in development of the technical requirements.