Digitally supported micro-volunteering – a report of an evaluation

November 23, 2021

Part One: Introduction

In August 2020, NHSx (in partnership with NHS England and NHS Improvement and the Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government) asked the Health Innovation Network (HIN) to undertake an evaluation to better understand digitally supported micro-volunteering models operating in the field of health and social care. This report presents learning from the evaluation and is aimed at an audience of commissioners and policy makers to inform their strategies around micro-volunteering.

Background and context

Micro-volunteering is a form of volunteering that comprises short and discrete activities, that can be easily accessed and completed by volunteers in a way that is informal and convenient – usually via digital platforms1. These characteristics distinguish it from traditional volunteering which typically involves the volunteer committing a regular block of time, over a longer period of months or even years. Micro-volunteering is a relatively new approach to volunteering2. A 2019 survey by the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) found that 23% of people exclusively volunteer as part of a one-off activity or dip in and out of activities3.

It has been suggested that micro-volunteering has the potential to increase volunteering activity, engage more volunteers, increase volunteer inclusivity, and provide a gateway into other volunteering roles. Consequently, it could increase capacity and meet the needs of a greater number of recipients. Emerging technology and societal changes, such as patterns of working, attitudes towards volunteering, and levels of community engagement, has increased demand for micro-volunteering, and there is growing recognition of its benefits4.

From March 2020, the coronavirus pandemic created severe disruption which interrupted the usual service delivery to broad sections of the population who require support with daily living. As large numbers of people were required to self-isolate due to symptoms or exposure to those with symptoms, and those most vulnerable to infection forced to shield, the pandemic created a greater need for support services, whilst concurrently constricting formal and informal networks through which those needs would usually be met5. The ELSA COVID-19 Sub-study conducted in June/July 2020 provides useful data around these patterns in people aged 50 and over who volunteer and/or provide care 6. The study found that of caregivers who looked after anyone once a week or more, inside or outside their household prior to the coronavirus outbreak, 35% either decreased or stopped the amount of care provided. It also found that almost 61% of those who had volunteered prior to the pandemic said that they either reduced (18%) or stopped (43%) taking part in voluntary work, with only 9% increasing their level of engagement, with the reduction most pronounced in those aged 70 or older.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic through initiatives such as TechForce19 and the NHS Volunteer Responder scheme led to increased interest in the potential value of micro-volunteering across health and social care. In response to these opportunities, new products supporting micro-volunteering have been introduced to the market. Suppliers have developed micro-volunteering platforms that operate different models. Some are ‘pull-based’ models where tasks are pulled by volunteers from browsing available opportunities; whereas others are ‘push-based’ models where tasks are pushed to the ‘best match’ volunteer to accept or decline.

Evaluation methods

The evaluation took a mixed methods approach gathering quantitative and qualitative data. It focuses on five platforms as case studies, exploring two in detail: the GoodSAM app which was integral to the NHS Volunteer Responders (NHSVR) programme and Team Kinetic; and three in less depth: Be My Eyes, Nyby and Tribe. Platform selection was informed by a rapid market review undertaken in August-September 2020.

This report draws on the findings from data gathered from multiple sources for the evaluation between October 2020 and February 2021:

- Interviews with representatives from the five case study platform providers and their clients/commissioners

- Interviews with NHSVR (n=17) and Team Kinetic (n=13) volunteers 7

- Surveys of NHSVR (n=12,056) and Team Kinetic (n=144) volunteers8

- NHSVR and Team Kinetic platform data about volunteer activity

References

1 The value of giving a little time: Understanding the potential of micro-volunteering (2013)

2 Jochum V and Paylor J (2013) New ways of giving time: opportunities and challenges in micro-volunteering: A literature review. Nesta, NCVO IVR. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/new-ways-of-giving-time Accessed: 07/05/21

3 Time well spent: A national survey on the volunteer experience (2019)

4 Time well spent: A national survey on the volunteer experience (2019)

5 Lachance EL (2021) COVID-19 and its Impact on Volunteering: Moving Towards Virtual Volunteering, Leisure Sciences, 43:1-2, 104-110, DOI: 10.1080/01490400.2020.1773990 [1] Chatzi G, Di Gessa G, Nazroo J (2020) Changes in older people’s experiences of providing care and of volunteering during the COVID-19 pandemic https://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/covid-19-reports

6 The concept of a healthcare system collectively gathering information and synthesising knowledge about how well or otherwise service delivery is working then using this understanding to drive ongoing improvement can be described as a ‘learning healthcare system’. The Institute of Medicine defines a learning healthcare system as a system in which “science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.”

7 In December 2020 and January 2021, the HIN evaluation team interviewed 17 people who had registered as volunteers with the NHSVR Programme (I1-17) and thirteen people who had registered as volunteers with one of three organisations using the Team Kinetic (TK) platform to support micro-volunteering: Cardiff (n=2), Kenilworth (n=9) and St Helens (n=2).

8 The survey analysis and reporting address the large variation between the sample numbers for the NHSVR survey compared to the Team Kinetic survey by first analysing differences in responses between the two sample and only presenting the aggregated response where there are no statistically significant differences between the two.

Part Two: Description of the platforms, their development and implementation

Five organisations supplying a digital platform that supports micro-volunteering in the field of health and social care were selected as case studies for the evaluation. The five platforms share common features, but also have unique distinguishing features which led to their selection as case studies during the scoping phase.

Platform core features

The five models all allow discrete, one-off task-based volunteering activities that put the volunteer directly in contact with the individual recipient to provide support for needs related to their health and social wellbeing. Table 1 provides a summary of the core features of each micro-volunteering model.*

- GoodSAM** was commissioned by NHS England and NHS Improvement to adapt its existing Emergency Responder technology to deliver the NHS Volunteer Responders (NHSVR) programme as a national COVID–19 pandemic response (https://nhsvolunteerresponders.org.uk/). The NHSVR programme was designed to provide a safety net to meet community needs in areas where voluntary sector infrastructure was inadequate to meet demand during the pandemic. It is commissioned by NHS England and NHS Improvement and delivered by Royal Voluntary Service (volunteer management) and GoodSAM (platform provider). Volunteers currently deliver seven roles: shopping for food and essentials and collecting and delivering prescriptions for someone who is isolating or shielding (Community Response and Community Response Plus), telephone support (Check in and Chat and Check in and Chat Plus), Patient Transport, NHS Transport and COVID vaccination centre stewards.

- Team Kinetic (https://teamkinetic.co.uk/) is a software development company offering volunteer management services, originally as a commission by Manchester local authority to meet the volunteer needs of the 2012 Olympics. The micro-volunteering functionality was developed to support their volunteer organisation clients changing needs in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Team Kinetic worked in partnership with existing clients to develop a ‘community task’ feature to facilitate micro-volunteering activities. The product development was also supported by the TechForce19 innovation grant. Volunteers deliver four categories of activities: collecting shopping and prescriptions, making wellbeing telephone calls, acting as a chaperone, and ‘other’ (befriending, technical support with setting up IT and undertaking odd jobs).

- Be My Eyes (https://www.bemyeyes.com/) is a video call service supporting people with visual impairment with everyday tasks such as reading labels when shopping or cooking or choosing the right clothes for work. The app connects volunteers with people needing support, allowing requests for help to be met within seconds. People with a sight impairment register their request for support on the app and the notification is then pushed out to volunteers. A direct video contact is then established between the person requesting support and the first volunteer to accept the support request undertakes the task. As well as this ‘first volunteer’ type of task, the app also enables people to request ‘specialised support’ that links them to organisations, such as the RNIB.

- Nyby (https://Nyby.com/about-Nyby) is a platform that facilitates task sharing across the health and care sector. Nyby enables professionals in the sector to obtain support from volunteers and other health and care personnel in meeting the needs of clients that would otherwise go unmet. Staff post requests for support via the platform and these are picked up by volunteers or, where relevant, other personnel. Volunteers, who are qualified by the organisation they belong to, undertake activities such as running errands, providing practical assistance (e.g., changing light bulbs), acting as medical escorts, and helping clients to exercise and socialise. Volunteers can register to offer specific roles and recruitment campaigns can be created for specific target groups; they are sourced via voluntary organisations who are using the platform and as individuals unattached to any particular organisation. Nyby is a Cloud based Software as a Service (SaaS) platform based on peer-to-peer technologies that match needs and resources through digital platforms. A Norwegian initiative, Nyby is currently developing its first UK site. The platform was created through forming research and development partnerships to identify and then address fragmentation in public service provision. The company additionally supports partners in identifying service gaps that can be closed by connecting local authorities, health services, volunteers and the third sector to match resources and services using digital technology.

- Tribe (https://tribeproject.org/provider/) is a digital platform that connects people with a wide range of local support, including volunteers, community groups and approved paid support providers. Tribe enables volunteers to support people in their local community socially through chats as well as with practical tasks, including shopping and collecting prescriptions. Tribe aims to work in partnership with volunteering organisations to mobilise and upskill volunteers via digital training in order to tackle gaps in provision – ‘care dark patches’. Unmet community support needs are identified by mapping data from multiple sources using artificial intelligence and machine learning. The platform is now also being used for social prescribing to map community service provision. Tribe was selected as one of UKRI’s Healthy Ageing Trailblazers, as part of this the project will receive significant funding to further develop the paid ‘home care’ support functionality.

Notes

*The core features table (Table 1) is specifically focused on the use of GoodSAM in relation to the NHSVR app and does not mention GoodSAM functionality that was not built into the NHSVR app. GoodSAM built the NHSVR platform to NHSE specification and GoodSAM has other functionality that was not incorporated eg an inbuilt video system, a rewards system, and a feedback and a notes system.

**Throughout the report, the GoodSAM/Royal Voluntary Service platform is referred to as NHSVR to reflect the focus specifically on the way that GoodSAM facilitated that specific NHS programme in partnership with RVS.

Table 1 Core features of micro-volunteering models

| Feature | Be My Eyes | Nyby | Tribe Project | NHSVR* | Team Kinetic |

| Local vs national implementation | International | Local (national across Norway by the Norwegian Cancer Society) | Local | National | Local |

| Free to download app | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mobile phone app | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Platform can be accessed without a smart phone? | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Allows discrete /one-off task-based volunteering activities | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tasks geographically ‘local’ to the volunteer and recipient (within a few miles) | No (tasks delivered via video) | Yes | Yes | Yes (except telephone ‘Check in and Chat’ service where recipients / volunteers matched at a national level) | Yes |

| Task benefits an individual recipient | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (except NHS Transport role which supports an organisation e.g assisting GP practice moving equipment between NHS sites; and Vaccination Steward role which supports the vaccination centre) | Yes |

| Volunteer and recipient have direct contact (e.g., face to face, phone, electronic) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Operating in UK | Yes, national coverage | No, but pilots are in planning phase | Yes, currently operational in various UK regions | Yes, commissioned for England | Yes, currently operational in four areas across UK |

| Supports volunteering activities within health and care sector(s) | Yes (though health support needs met by organisational partners) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The ‘presentation of opportunities’ to volunteers (‘pull’ or ‘push’ models) | Push | Push and Pull. Requests are pushed as alerts via the app and volunteers can also search a list of requests. | Push | Push Pull functionality is used to enable vaccination centre volunteers to find shifts. | Pull via searchable ‘public’ list of tasks open to volunteers within a given proximity. Push notifications also sent via email. For Android users notifications can be pushed directly to the phone. Tasks also pushed to specific volunteers carrying out a ‘Street Champion’ role. |

| The setting of ‘preferences / constraints’ by a volunteer (e.g., for particular tasks, localities etc) | Yes (though limited to language spoken) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tasks can be booked and/or converted into a repeat or regular task | No | No – but function is in the ‘roadmap’ for development | Yes – integral | Yes – referrers can set a task as repeating but these cannot be carried out by the same volunteer more than twice in a month (except Check in and Chat Plus and Community Response Plus roles which allow ongoing support to be provided by the same DBS-checked volunteer). | Yes – allows volunteer to repeat/rebook tasks without need for administrative approval. All re-bookings are listed as new tasks so there is an audit trail, and they are picked up in the public bucket if not fulfilled. |

| Within app recording of tasks | Yes | Yes – system records activity of task, when and who carried out the request | Yes | Yes – volunteer asked to confirm task completed and referrer informed complete | Yes – volunteer asked to confirm task completed |

| Within app activity record available to volunteers | No. Volunteers can only access account creation details. Activity record is available on request from Be My Eyes. | Yes | Yes. Volunteers can access number hours logged into app and log of completed tasks. | Yes. Volunteers can access number of hours on call, 2-month log of alerts and completed tasks. | Yes. Volunteers can access completed or pending tasks (including type and date completed). Volunteers can export record and share this. |

| Within app screening and verification of a volunteer’s identity | Yes. 2 stage authentication during registration on the app. | No. Verification and screening is carried out manually by the commissioning organisation where required for a role. | Yes. Some checks can be completed through the app or website. Volunteers can upload ID/DBS documents via the app, but checks are carried out manually by the commissioning organisation. | No. Volunteers can upload ID/DBS documents via the app but checks are carried out manually by the organisation. Volunteers must complete a form and provide evidence of DBS accreditation for certain roles. An ID check is carried out on all volunteers as part of the application process. | No. Volunteers can upload ID/DBS documents via the app but checks are carried out manually by the commissioning organisation. Results of the checks recorded on the app. Next app iteration has a fully integrated DBS service with ID verification. Parental consent can be requested for younger volunteers as required. |

| Volunteer recruitment | Media (including social media) campaigns | Handled by the partner commissioning organisation. The platform includes the ability to generate bespoke registration webpages to aid recruitment. | Organisations form a team on the Tribe platform and register existing volunteers. Can invite individuals registered as a “regular joe” Tribe volunteers to join the team and promote the team via social media channels. | National / local call directing to website for online registration. | Four TK micro-volunteering projects recruited volunteers locally: direct email to existing volunteers, adverts in local papers, Facebook and flyers posted in public settings. |

| Volunteer registration | Within app registration system | Sign up via website or app – only a name and phone number are needed, excluding any further documentation requirements set by partner organisations. | Within system application process | Direct registration on the website. | In-app registration by the volunteer or client and bulk registration by Team Kinetic from client list. In-app registration collects name, address, age which TK verify to client specification. Uses single sign-on so volunteers can use Google or Facebook to login and confirm their email address. In four TK micro-volunteering projects, volunteers registered initially on another website or Facebook and delivery organisation created TK accounts on behalf of volunteers following completion of ID and security checks. Volunteers were then asked to download the app. |

| Training and induction (on- or off-line) | Yes – via online training resources available through Be My Eyes website and app. | Locally determined based on need (i.e., by working with local partners). Dedicated Customer Success Managers help with training local teams and resources (including video content) is available for supporting professional care staff and volunteers. | Yes – via online training resources available through Tribe website and app. Volunteers register for training via the app/website and it is delivered via the platform. In-person training will resume when feasible. Tribe will then work with training providers to upload records to volunteer profiles Upskilling volunteers to meet community demand is integral to the Tribe Project. Training is developed and delivered in collaboration with voluntary/community sector, and commissioner partners and supported by industry partners such as Skills for Care. | Yes – via online training resources available through NHSVR website. RVS deliver all training which takes the form of volunteer ‘guides’, pre-recorded webinars, live webinars, links to external websites/training providers. | Yes – via online training resources available through TK website with API and Zapier integration to external resources. Admin users can build specific induction and onboarding for specific roles. Client may also offer training outside of system. Volunteers and Admin users can upload documents to individual training profiles and to opportunities. TK have offered providers bespoke training sessions over Zoom. |

| Support for volunteers | Support provided via the Be My Eyes customer support team (by email and through the app). | There is an assigned project manager within the local organisation who acts as support for their volunteers. Nyby provide technical support with regard to the system. | Tips and instructions are shown within the app. Tribe deliver on-boarding training for new voluntary organisations/areas, targeting less digitally savvy users. The wider support offer for volunteers is still being shaped through co-production with stakeholders. | A RVS call centre offers volunteer support seven days a week, 08:00-20:00. Specialist teams (e.g., Safeguarding) are available to escalate callers to if their requirements cannot be met by the general Support Team. | Team Kinetic support the Admin level users (clients) to enable them to support their users directly. Issues can be escalated via support tickets and support chat to a Team Kinetic support operative. |

| Creation of tasks | Support needs are posted directly by recipients | Anyone in a group with permission can create a task | Tasks created by partner organisation representatives | Any professional can request support for a recipient via webpage or phone, and system extended to include self-referral | Volunteer managers triage and create tasks |

Implementation

The geographical scale and boundaries of the models vary between (inter)national and local communities.

A co-production approach is at the core of how Nyby and Tribe implement their models. This involves working with local community groups to map local need and tailor the technology based on local contextual factors. Nyby work with local communities to map local needs and only expand based on pre-defined success criteria. Local partners working with Nyby often appoint a Project Manager who works closely with a Nyby Solution Specialist to ensure that any necessary training is completed and there is a rigorous implementation and roll-out plan. Nyby also enables and promotes experience sharing across its 50 government and charity partners across Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany and soon, the UK. Tribe work with local stakeholders to use local data to develop a ‘community needs matrix’ displaying projected need versus current provision. Tribe expect a minimum of a two-year commitment from commissioning organisations recognising the time it takes to bring new community provision online.

Part Three: Learning from volunteers about facilitating micro-volunteering using digital platforms

This section of the report explores the learning from data about the activity, experiences and perceptions of volunteers with the NHSVR and Team Kinetic platforms. It draws on platform system data, and feedback from volunteers via surveys and interviews.

Volunteer activity with the micro-volunteering platforms

There is considerable appetite for volunteering with digital platforms that support micro-volunteering.

Data extracted from the NHSVR and TK platforms (Table 2) shows that up to January 2021 just under 800,000 people had registered with the two platforms, from the point early in the pandemic (March/April 2020) when the micro-volunteering platforms were launched.

| Activity unit | NHSVR9 | Team Kinetic10 |

| Approved volunteers | 647,405 | 155,322 |

| Volunteers who put themselves ‘on duty’ | 397,940 | |

| Created tasks | 1,766,210 | 4,710 |

| Completed tasks | 1,446,681 | 4,615 |

| % of tasks completed | 81.9% | 98.0% |

| Avg. monthly completed tasks[11] | 144,981 | 506 |

Volunteers’ motivation for signing up with the platforms needs to be seen in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

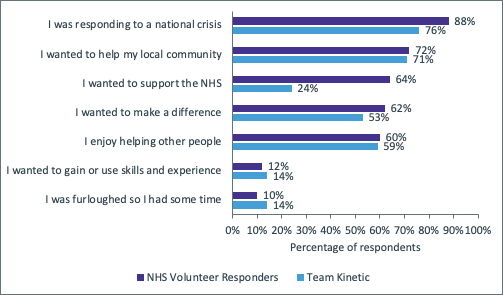

As shown in Figure 1, the main reasons reported by NHSVR and TK survey respondents for registering to volunteer with the platforms were related to a desire to help during the COVID-19 pandemic. Responses to this question need to be understood in the context of the platforms’ development. The NHSVR and Team Kinetic platforms were both developed specifically as a solution to problems created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHSVR programme recruited volunteers through a very prominent national media campaign with messaging around creating an ‘army’ of NHS volunteers to support the NHS through a crisis. In contrast, Team Kinetic worked with local organisations to develop locally relevant responses to mobilise volunteers to provide support during the crisis.

References

[9] NHSVR data was extracted from the Future NHS NHSVR project site for all activity from 30th March 2020 to 25th January 2021. ‘Approved’ and ‘on duty’ figures were taken from: https://www.royalvoluntaryservice.org.uk/Uploads/Documents/Our%20impact/NHSVR_Working_Paper_Four_Patient_Findings.pdf

[10] Team Kinetic data was extracted for all activity from 6th April 2020 to 26th January 2021

[11 Based on data trimmed to include whole months only from 1st April-31st December 2020.

Qualitative data from interviews with NHSVR and TK volunteers provides additional insights. Most NHSVR interviewees first heard about the initiative from the national media campaign. In contrast, recruitment to the TK platform was very much implemented at a local level. Kenilworth interviewees received an invitation to sign up to Team Kinetic from the local Covid-19 Facebook group they joined early in the pandemic. Cardiff and St Helens interviewees responded to adverts in their local papers, Facebook and flyers posted in public settings, and to information received from the local volunteer centre. One interviewee had first used the Team Kinetic platform in 2012 when it was rolled out for volunteers attending sporting events to replace communication with the volunteer force by email, though she had not used the app previously.

In addition to wanting to help out in the crisis, being in a position to help was a key theme in interviewees’ motivations. Interviewees talked of having more time for a range of reasons related to activities being restricted during the pandemic. Decreased work commitments were mentioned frequently, including working from home, and other volunteering work being paused or moving online. Interviewees also reported feeling they had relevant skills to help.

Platforms that facilitate micro-volunteering have the potential to provide a significant level of support during a crisis.

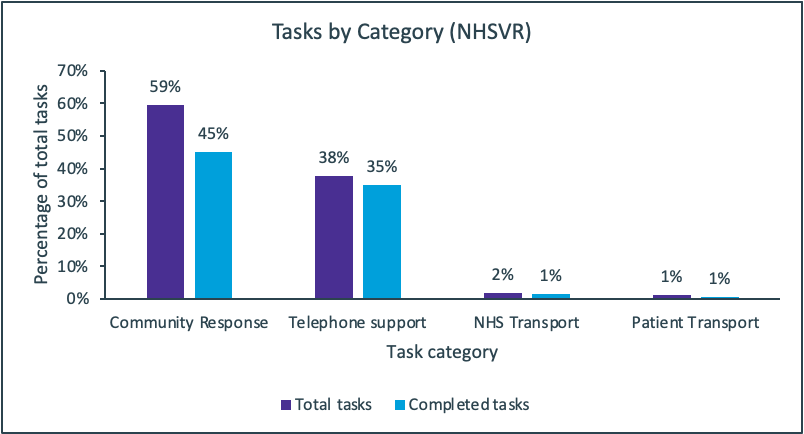

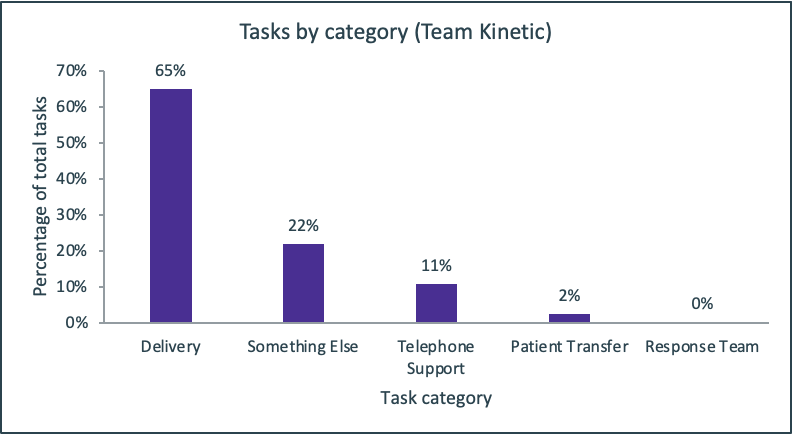

Whilst not all those who registered with the NHSVR and TK platforms were approved to volunteer or went on to download the apps and then complete tasks, the platform data indicates that over 100,000 individuals carried out over 1.5 million tasks between March/April 2020 and January 2021 (Table 2). The majority of these tasks were either delivery of shopping, prescriptions, and other essentials or telephone support (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

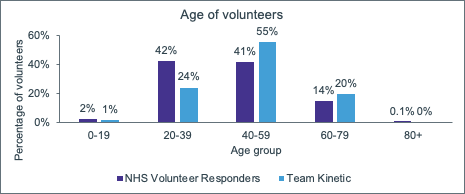

Digital platforms that support micro-volunteering have the potential to engage a broad demographic

As illustrated in Figure 4, NHSVR and TK platform data shows that around 80% of registered volunteers were of working age (20 to 59).

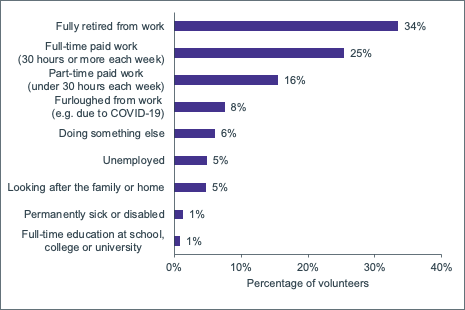

69% (268) of Team Kinetic volunteers were female and 31% (123) were male. No other platform data was available on volunteer demographics, but data from the NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteer surveys shows: 64% of respondents were female; 6% were from an ethnic minority community (EMC) group (indicating an ethnic group other than ‘White UK’); 63% stated a religion; heterosexual and 4% identified their sexuality as LGBT+ (as opposed to heterosexual). As shown in Figure 5, 25% of respondents were working full time and another 16% were working part time; 9% were furloughed and 5% were unemployed.

The NHSVR programme recruited volunteers through a very prominent national media campaign with messaging around creating an ‘army’ of NHS volunteers to support the NHS through a crisis. The messaging may have attracted a younger cohort of volunteers than the TK micro-volunteering platforms with their very local focus.

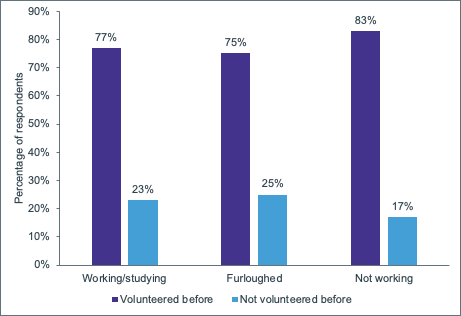

Digital platforms that support micro-volunteering have the potential to engage people who have not previously volunteered.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteer surveys found that around a quarter of respondents who were working or furloughed had never volunteered before. A similar pattern was seen in the qualitative interviews with volunteers from the two platforms. Interviewees who had not volunteered in the past were asked why and their reasons included not knowing how and a lack of time when working full time was the main reason. The micro-volunteering apps addressed these issues because people were able to find and complete tasks at the time allocated to volunteer.

In addition to quantitative data from surveys of NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteers, rich material from interviews with volunteers from those platforms help us understand the way in which micro-volunteering engages people – both those who would not traditionally volunteer, as well as those who are already active volunteers. Table 3 compares what we learned from NHSVR and TK volunteers with the findings from the 2019 ‘Time Well Spent’ national survey on volunteer experience.

Table 3 What micro-volunteering offers for those who are traditionally less likely to volunteer

| What the evidence tells us about…. | |||

| Volunteers with a micro-volunteering platform (from this evaluation) | Traditional volunteers (from Time Well Spent: A National survey on volunteer experience. 2019) | The opportunities micro-volunteering (MV) offers for those who are less likely to volunteer due to this characteristic | |

| Characteristic | |||

| Age | From Team Kinetic and NHSVR platform data we know around 80% of volunteers with both platforms are of working age (20 to 59). 77% of respondents to the NHSVR survey were aged 16-64; 23% were aged 65 or older. | People aged 65 and over were the most likely to have volunteered recently: 45% saying they had volunteered in the last year. People in this age group were most likely to volunteer frequently (35%). The proportion of those who had volunteered in the last 12 months was lowest among 25–34-year-olds (31%) and generally lower for people aged 25 to 54. | The speed with which MV tasks can be accessed and carried out addresses barriers to involvement in traditional volunteering in working age people. Specifically, it allows activity around work/family commitments, and leisure/lifestyle choices. |

| Gender | From Team Kinetic platform data, we know 69% (268) of volunteers were female. 64% of respondents to the NHSVR survey were female. Our volunteers’ surveys found: 1. The NHSVR and TK platforms were good at engaging men who had not previously volunteered: 25% said they had never volunteered before Covid-19 compared to 17% of women (Q1). 2. Men tended to sign up for different activities than women (Q6): they were more likely to sign up for community support (e.g., shopping), patient transport, or other transport; and less likely to sign up for telephone support (32% compared to 66% of women signed up for this). 3. Men were likely to have completed fewer tasks (Q8b): 42% had completed no tasks and 18% had completed over ten tasks (compared to 34% and 15% of women respectively). This may be a function of the type of activities they signed up for as compared to women they were more likely to say, ‘I haven’t yet been given a task to do despite switching the app ‘on-duty’’ and less likely to say, ‘I was given a task but unable to accept’ (Q9). 4. When asked to indicate reasons why they would continue to volunteer with the platform in the future (Q16), men were more likely to select ‘a sense of duty or obligation’ (43% compared to 22% of women). | Women are more likely to volunteer. Men were more likely to say they have never volunteered (34% vs 29% of women). Men who have volunteered were more likely to say they have been hardly involved throughout their life (23% vs 19% of women). | MV can provide access to opportunities to carry out tasks that may be of interest / relevant to skills and experience. |

| Ethnicity | Our volunteers’ surveys found: 1. 6% of respondents were from an ethnic minority community (EMC) (compared to 15% in the general population according to the 2011 Census). As previously discussed, this could just reflect what we know to be lower response rates amongst EMCs. 2. EMC respondents were as likely as those of a white ethnicity to have volunteered in the past (Q1): 80%. 3. As reported above, compared to those from a white group, EMC respondents were likely to indicate different reasons for being motivated to volunteer with the platform (Q5), and to report differently in terms of their experience of volunteering with the platform, particularly in terms of the benefits and rewards (Q13). Overall, they seemed more likely to be satisfied with the experience. | Rates of recent volunteering in people from ethnic minority communities (EMC) are similar to people who were white (36% compared to 38% respectively). | MV can provide access to opportunities in a way that seems to meet the expectations of people from EMC groups. |

| Working status | Our volunteers’ surveys found: 1. 25% of respondents were working full time and 16% part time; 8% were furloughed and 5% were unemployed. 2. 26% of respondents working full-time, and 25% of those who were furloughed from work or unemployed had never volunteered before (Q1) (compared to 16% of the retired); interestingly, 20% of those who were permanently sick or disabled had never volunteered before. | Unemployed people and those not working are least likely to have ever volunteered. People working full time were less likely to have volunteered in the last year (35%) than those working part time for 8–29 hours a week (41%) or fewer than eight hours a week (53%). They were also less likely to volunteer than retired people (44%) or full-time students (42%). | The speed with which MV tasks can be accessed and carried out addresses barriers to involvement in traditional volunteering in working age people. Specifically, it allows activity around work/family commitments, and leisure/lifestyle choices. |

Digital platforms that support micro-volunteering offer volunteering activities that are complimentary to those offered by more traditional forms

Asked how their previous experience of volunteering compared to experience with the platform, interviewees said it was difficult to compare them. For example, one said it was a different type of volunteering in that her governor roles are regimented by attending meetings, whereas the app allowed unplanned support to individual needs. Another said that compared to her trustee and teaching voluntary work, the difference is that she can choose to do one off activities. There was recognition of the specific context in which the micro-volunteering platforms were operating: the situation was different, and the app worked well in organising people and getting them mobilised to help out in the crisis.

Interviewees saw advantages and disadvantages of micro-volunteering compared to their more formal volunteering activities. They described how although they liked the freedom of not making a commitment offered by the platform, they preferred their other volunteering work as it offered routine and certainty. However, the also talked of the benefits these features brought in terms of planning activity around other commitments. It was suggested that the more formalised commitments associated with traditional forms of volunteering guarded against the experience through the platforms of offering help but not being called upon. One volunteer also described traditional volunteering as a preference due to the wider variety of tasks usually on offer. Others contrasted the social contact and teamwork in their roles outside the platform with the absence of a team with the volunteering model offered by the platform.

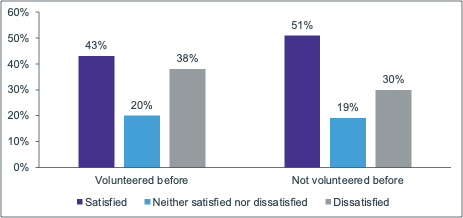

In the qualitative interviews with NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteers, those with considerable experience of traditional models of volunteering were notably more critical of various aspects of these micro-volunteering platforms. This finding is supported by evidence from the surveys as shown in Figure 7.

Digital platforms that support micro-volunteering have the potential to engage volunteers beyond the pandemic

72% of NHSVR and Team Kinetic survey respondents indicated they would be ‘likely’ to volunteer with the platform in the following twelve months. A similar pattern was seen in the qualitative interviews. Some of those who said they would continue to volunteer with the platforms beyond the pandemic added the proviso that the amount of time they could offer might reduce, for example because of changing work commitments.

Reasons given in the interviews for continuing to volunteer with these micro-volunteering platforms included the flexibility – being able to switch the app on and off, and that it was undemanding, and fit with their availability, and met their interest in short activities involving no commitment; and the ease of using the app.

Most interviewees also said they might look for new opportunities for volunteering, outside of their activity with the platform.

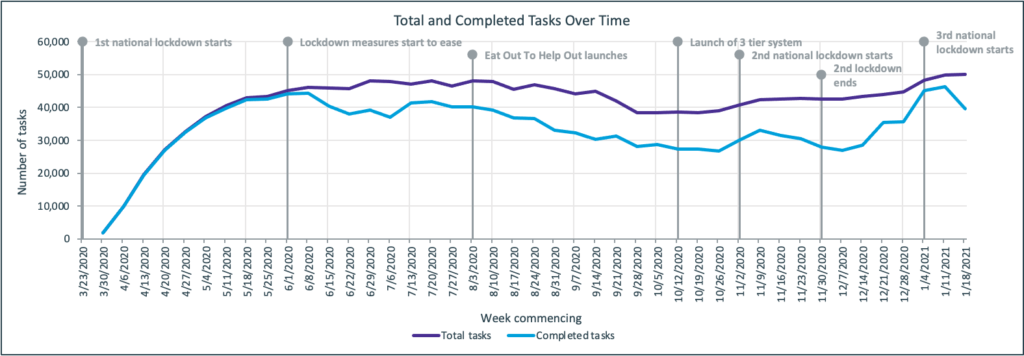

Frequency of volunteering is linked to an individual’s availability

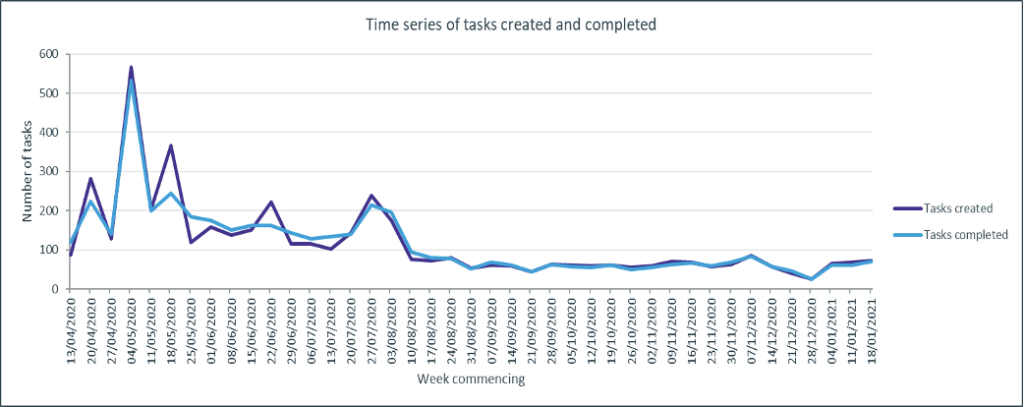

In qualitative interviews, NHSVR and TK volunteers indicated that the frequency with which they volunteered with the platforms was dependent on their availability and the ability to fit tasks in with personal circumstances (e.g., health), other commitments (particularly work – both paid and unpaid, including family care, but also education), and lifestyle (e.g., social and leisure pursuits). Changes in the extent of activity of volunteers with the NHSVR and TK platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights how availability alters over time. The timeline graphs with activity mapped against the pandemic milestones (Figure 8 and Figure 9) shows there were more uncompleted tasks as the lockdown eased. In interviews, volunteers described how the number of tasks they undertook rose/fell over time as the demands of their work (paid and unpaid) decreased/increased. Some had reduced their volunteering activities during the summer months when COVID lockdown restrictions eased, and they were able to do more socially.

Volunteers experiences with the micro-volunteering platforms

On the whole, NHSVR and TK interviewees were positive about their experience of volunteering with their respective platforms.

A cross-cutting positive theme in the qualitative interviews with NHSVR and TK volunteers was the simplicity of the approach in general and specifically of the apps and the tasks they supported. People liked the online system and the accessibility offered by a phone-based app. In terms of the broader approach, interviewees liked its flexibility which allowed task selection to fit with availability and being able to choose tasks. Feedback from NHSVR and TK volunteers in both the surveys and interviews was broadly positive about registration and using the app to find tasks.

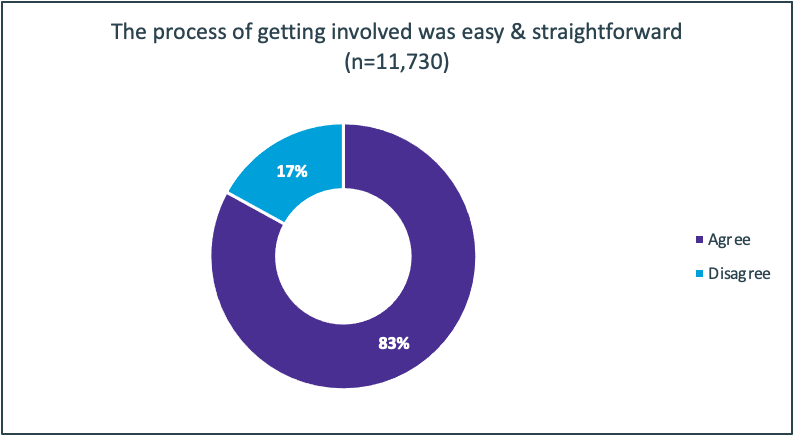

As shown Figure 10, the NHSVR and TK volunteer surveys indicate that 83% of respondents found the process of getting involved ‘easy and straightforward’. A similar pattern to that found in the volunteer surveys was seen in the qualitative interviews, with one NHSVR interviewee indicating it took twenty minutes to register.

Both NHSVR and Team Kinetic interviewees generally found the respective apps easy to use, though some had experienced difficulties initially before gaining familiarity, and/or knew of others who had been unable to use it.

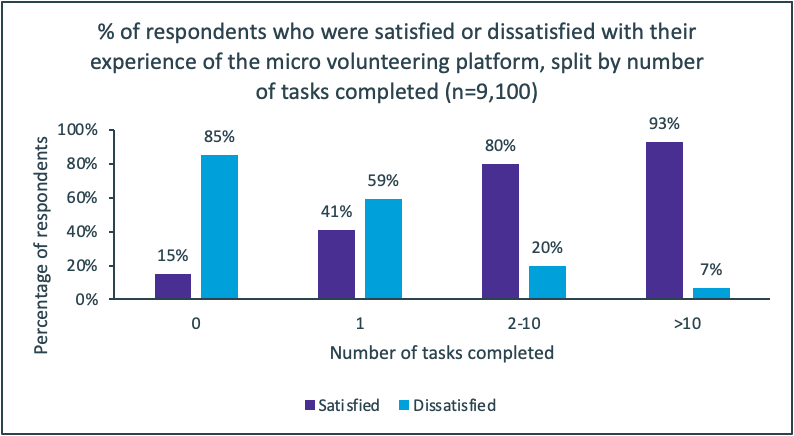

Dissatisfaction was largely associated with low activity

In the qualitative interviews with NHSVR and TK volunteers, dissatisfaction was largely associated with low activity, caused by receiving no or too few alerts and Figure 11 illustrates how the survey findings support this observation. Interviewees who had completed no or few tasks reported disappointment, and feelings of having wasted time.

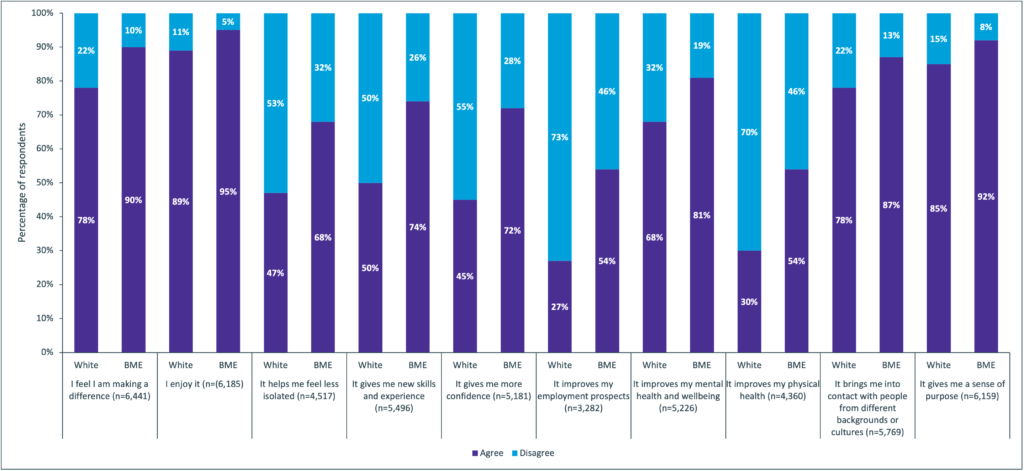

There were variations between ethnic groups in responses to questions in the volunteer surveys which suggest that, compared to those from white ethnic groups, ethnic minority communities had particularly positive experiences

Analysis of data from the surveys of NHSVR and TK volunteers found a statistically significant difference in responses given by respondents from ethnic minority communities (EMCs) compared to those from a white ethnic group on a number of questions. A detailed breakdown of the difference between white and EMC responses to a set of questions about experience with the platforms is given in Figure 12.

Additionally, 64% of EMC respondents agreed with the statement ‘I have benefited from gaining new skills and knowledge through the guidance’ compared to 45% of those from a white ethnic group. 74% of EMC respondents agreed experience with the platform ‘gives me new skills and experience’, 72% agreed ‘it gives me more confidence’, and 54% agreed ‘it improves my employment prospects’. The respective figures for white respondents were 50%, 45%, and 27%.

EMC respondents were also more likely to say they would be ‘likely’ to continue to volunteer through the platform over the next twelve months: 84% compared to 72% of respondents from a white ethnic group.

Volunteers’ tips for implementing a micro-volunteering platform

In the qualitative interviews, NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteers made suggestions for improvements to the platforms which are presented here.

General improvements

Volunteers indicated that ensuring the frequency of activity matched their expectations would enhance their experience of volunteering with these micro-volunteering platforms, as would minimising time between registering and approval and commencement of volunteering activities. They suggested that providing clear role descriptions at registration would help volunteers select roles, and that clear guidance around carrying out roles would be beneficial, such as arrangements for handling payment for shopping, and where to access support where needed to carry out roles. Simple mechanisms for claiming reimbursement of volunteer costs was also indicated.

Interviewees noted that being able to view locally relevant communication, as opposed to receiving blanket information, would be helpful, increase the user experience and create a team feel. It was suggested that building a volunteer network, both locally or on a wider scale, would be beneficial for building rapport among volunteers and improving peer-supported learning. The use of online forums such as Facebook were seen as a way to achieve this, with interactive training materials to support peer-learning and increasing skills. Having access to local and/or regional support networks of delivery managers was also identified as having potential benefits for the volunteer experience.

There were perceptions that both platforms could be expanded to capture a wider variety of tasks and allow tasks for individual clients to be repeated. It was suggested that notifications should be redesigned to give clearer and more localised messaging. For example, using a push model if there is little demand in one area, to notify volunteers that they may not be needed and keep people informed. Alternatively, using a pull model where specific tasks can be grouped and completed by a small number of individuals or to increase continuity.

Finally, there was a perceived need to connect to a wide source of ‘referrers’ such as community services, social services and GPs, to reducing the burden on these service providers.

Improvements to the technology

Volunteer suggestions to improve the technical aspect of the apps mainly related to the presentation of tasks. Providing additional details regarding the task, including detailed description and estimated time for completion, would enable volunteers to make a more informed choice about accepting or declining a task. Inclusion of information about the client within the alert/notification was suggested to enable the volunteer to tailor their response to the individual client e.g., information about the age of the client, if they have a hearing impairment or dementia, or having difficulties communicating in English. TK volunteers suggested grouping tasks within a small locality would help volunteers identify opportunities in their locality. Suggestions for modifications to the NHSVR alert system included changing the tone and volume of notifications and introducing the ability to restrict the number of alerts.

NHSVR volunteers felt the app reporting could be improved by allowing volunteers and clients to enter feedback on tasks completed, providing an audit trail which could be accessed by both, as well as ensuring that unnecessary alerts being issued for clients who no longer needed the service. In-built metrics such as ‘hours spent available via app’ are not as useful to volunteers who wish to track number of tasks completed for example. Availability of record of activity in a format which could be exported and shared on CV to support employment search was identified as beneficial.

There were also suggestions to improve external communication via the app. Firstly, linking the chat feature to a specific task rather than showing continuous chat data. Secondly, allowing the app to integrate with Zoom/ virtual video calling platforms for use during ‘check in and chat’ tasks which would allow for a more personal experience for both volunteers and clients. Thirdly, a mechanism to escalate a task to a help centre after several failed attempts to contact a client.

Both NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteers suggested a need for more support regarding navigating the app for individuals who are perhaps less technologically trained. This could be achieved through tutorials or user guides within the apps themselves.

Techniques for providing rewards like virtual badges

The Team Kinetic task-app already incorporates a reward system which includes virtual badges of achievement. In contrast, the NHSVR app has no virtual reward recognition system built in. Views across volunteers were mixed in terms of the utility of virtual rewards. Both volunteer groups acknowledged that virtual rewards such as badges could be motivational for some individuals.

Team Kinetic volunteers noted having a wider variety of milestones than currently available may be useful, such as recognition when reaching a certain number of service users or incorporating a tiered system which volunteers climb as they complete tasks (e.g. bronze, silver, gold). There was also recognition that receiving an accolade in the form of virtual ‘thumbs-up’ from a volunteer coordinator had been a boost during their volunteering experience, as had receiving a thank you letter from a local mayor. NHSVR volunteers acknowledged that a reward system could be a nice addition to the current app and that a competitive element may motivate some individuals, in particular, it may be rewarding for completer-finisher type personalities. NHSVR volunteers had fewer practical ideas about what the reward system should measure, perhaps due to the fact they had not experienced this during their usage of the app.

Some volunteers across Team Kinetic and NHSVR expressed concern over the reward system stating that volunteering should not be used as a means to gain rewards, and those wanting to help would not likely be interested in such rewards. This type of system may also lead to a focus on quantity rather than quality. Despite this, it was acknowledged that a reward system could still help engagement with volunteering and for individuals wanting to use this information on their CV.

Improving opportunities for volunteers to take part in micro-volunteering

Both Team Kinetic and NHSVR volunteers noted a need for increased awareness of the micro-volunteering model. Suggestions were made to invest in marketing such as TV advertisements and local media opportunities and that volunteer-led campaigns may be beneficial in recruitment. NHSVR volunteers noted that general communications had been too corporate to date and did not focus enough of the communities being served and stated there is a need to provide regionally relevant feedback to local groups volunteering. Practical suggestions such as expanding the types of tasks available and capitalising on the local expertise could improve opportunities for volunteers and clients alike. Additionally, obtaining feedback from both volunteers and service users was mentioned as a means to improve the current system.

Team Kinetic volunteers noted a need for clearer governance structures to ensure public safety and the benefits of sharing good practice across volunteer organisations to avoid potential mistakes. Similarly, to NHSVR, Team Kinetic volunteers also suggested a way to capture and organise disparate groups during emergencies (e.g. floods) could be beneficial and potentially easy to integrate into the TK system.

Volunteer perceptions of micro-volunteering

There was consensus across interviewees from both platforms that most of the different key features of micro-volunteering were important to them

In the qualitative interviews, NHSVR and TK volunteers’ perceptions of different aspects of micro-volunteering were explored. Interviewees wanted to be able to volunteer in a way that involved ‘small actions that are clearly defined, can be completed quickly, and have a clear beginning and end’, and to be able ‘to choose an action and complete it when it is convenient’. The main reason they gave was the flexibility this provided to complete tasks within the time allowed by other commitments. There was also consensus that an approach involving ‘actions that can be completed at home or close to home’ was important, most often because of accessibility.

Views about the importance of volunteering involving ‘no commitment from the volunteer to complete the action more than once – involvement can be just a one-off or volunteers can dip in and out’ were more divergent. Whilst this brought benefits for some, once again, largely around ‘flexibility’, others saw advantages for both clients and volunteers in repeating tasks – to build trust, establish rapport and improve understanding of how the volunteer can help.

There were also diverging views around the recruitment process and training. Interviewees wanted a ‘simple process of identifying an opportunity for volunteering without a complicated recruitment process’, because it saved time which could be used to volunteer, whereas complicated processes could put people off. However, adequate governance and training were regarded as important. This suggested the need for a balance between simplicity and ensuring that the service was delivered safely, perhaps though an approach that was more tailored to the task and the volunteer.

Volunteers like the accessibility and flexibility of micro-volunteering

Volunteers like the accessibility of micro-volunteering – tasks can be easily identified and quickly completed at a convenient time. They also like the flexibility it offers – to choose the extent of commitment, over a time-limited period, in a way that fits with their lifestyle. People liked that they could decline a task, knowing that someone else would pick it up – people in need would not be left without. People like being able to choose and carry out different types of tasks offered by the platforms. Micro-volunteering was described as a good way to get volunteer experience, and a good entry point for people who did not know how to volunteer.

The micro-volunteering concept underpinning the NHSVR and Team Kinetic programmes did not suit all interviewees

Some NHSVR volunteers said they would prefer a mechanism that enables them to establish a relationship with a client over time, to improve rapport and understanding of the client’s needs and one said they would prefer to sign up for a specific shift and receive a list of shopping tasks to undertake during that shift. Team Kinetic interviewees mentioned features that were specific to the way the app was used locally that addressed these areas of dissatisfaction expressed by volunteers with the NHSVR Programme. Notably, they talked about the ‘street champion’ role with multiple tasks grouped at a street level; and being able to book to repeat tasks which could build rapport with clients.

There was a perception that micro-volunteering is a good way to mobilise people into volunteering, especially during the current crisis. However, some experienced volunteers personally preferred the more structured commitment of traditional volunteering models.

Push vs pull models of micro-volunteering suit different people at different points in time

Interviewees were asked for their views of push and pull models of micro-volunteering platforms. Responses to this question revealed some key differences between the NHSVR and Team Kinetic platforms.

NHSVR interviewees agreed that the platform was a ‘push’ model of micro-volunteering. Their perceptions of the ‘pull’ model in comparison to their experience of working with the ‘push’ model were mixed. There was, however, a clear preference for the ‘push’ model amongst most interviewees at the current time: either in the short term because it suited their current circumstances, particularly work commitments, or in the longer term because it suited their attitudes to volunteering. NHSVR interviewees indicated they, and others, would have volunteered less if they had to actively search for opportunities, that the ‘push’ model made volunteering easier, and that people are more willing to help if asked. Just four people said the pull model would work better for them at present, including two who reiterated points made throughout the interview that they preferred to develop a relationship with a recipient over time.

Team Kinetic volunteers commonly thought that the platform involved both pull and push approaches. ‘Pull’ in that they could search for opportunities directly on the app. ‘Push’ in that delivery organisations sometimes sent them notifications outside of the app – by text, email, WhatsApp or from the Facebook group – that tasks were listed on the app for completion. Mixed views were expressed about preferences for ‘pull’ or ‘push’ models of micro-volunteering. Largely people liked the model they experienced, including those who liked the mix of the two approaches. One interviewee said that they liked receiving notifications, another said it would be helpful to receive notification that jobs are available by phone, as a reminder to look at the app, particularly when they returned to work full time.

Part Four: Sustainability

Supporting and promoting volunteer capacity

There is some concern amongst platform providers and their clients about volunteer fatigue and a consequent perceived need to build the voluntary sector infrastructure and continue to raise the profile of volunteering. However, the various platforms were seen as a good way to promote new models for volunteering and expand and sustain volunteering capacity. This was also a strong theme in the interviews with volunteers, many of whom pointed to the need to increase public awareness of the opportunities presented by micro-volunteering platforms. Across the board, volunteers highlighted how micro-volunteering has huge potential to support local communities and health economies in a number of ways, and that this has been largely due to a cultural shift observed since the pandemic.

The NHSVR and Team Kinetic volunteers interviewed particularly liked the flexibility and simplicity of the approach in general, and specifically the app. They saw both platforms as a way into volunteering for those without previous experience. Similarly, Be My Eyes reported volunteers liked the flexibility and simplicity of app, which leads to high retention and the sustainability of the model.

For Nyby and Tribe, the underlying rationale for their model of volunteering is to build and sustain volunteer and community capacity to address local need. Their approach uses co-production to embed a locally tailored model of volunteering within community partnerships by harnessing the power of technology and community action. Team Kinetic was used by local voluntary sector organisations and volunteers described some mechanisms that supported community development, such as the ‘street champion’ role, and local co-ordinators. There was a theme in interviews with NHSVR volunteers however, that the platform lacked sustainability because it was not embedded within existing local voluntary sector infrastructure, and therefore failed to develop social capital. Interviewees suggested this could be addressed creating local or regional structures, including mechanisms for teamwork and expert and peer support.

Volunteer passports

Platform providers and their clients highlighted the role digital platforms could play in expanding the development and roll out of volunteer passports. For example, if a volunteer registers with a platform, completes ID and DBS checks, this could potentially simplify and expedite the process of them registering and volunteering via another voluntary organisation/platform. In addition, it could provide volunteers with a digital ‘CV’ of their volunteering skills and experience.

Variation in model implementation

The flexibility in how the model and underpinning technology are implemented is an important factor in determining sustainability, because it allows clients and users to tailor the approach into local settings and ways of working (e.g., systems, processes, practices). Preventing the adaptation of a technology to local contextual factors is known to result in implementation failure[1]. However, local variation in how the model is implemented may result in the model being used less effectively or optimally. For example, there could be issues when platforms were seen as an adjunct to, rather than an integrated component of, the local volunteering pathway. This could be due to local organisations being unwilling or unable to change internal systems and process to achieve better integration. Examples of not fully utilising the platforms included, only putting a sub-set of pre-existing volunteering activity onto the system rather than using it to recruit, register and manage new volunteers; and using process to advertise tasks to volunteers outside of the platform (such as through a direct email) rather than using functionality within the system to alert volunteers to opportunities. It is important here to recognise that two of the platforms were developed specifically as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic is response context and that this has determined the way they have evolved. It is clear that these platforms will need to adapt to be relevant as a way of supporting micro-volunteering outside of an emergency.

Standards for micro-volunteering

There was a perceived place for standards in terms of increasing the confidence of commissioners regarding the quality of provision. Tribe are working with TSA (https://www.tsa-voice.org.uk/) as part of a steering group for digital care standards and are participating in Helpforce work on standards in volunteering (https://helpforce.community/about). However, BME expressed concerns that standards would introduce complexity in the system which would detract from the benefits of simplicity offered in their app. GoodSAM, the providers of the technology supporting the NHSVR model, expressed a similar note of caution regarding the responsibility of organisations in terms of supporting volunteers and enabling

References

[12] Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies (Greenhalgh et al 2019)

Part Five: Conclusions and Recommendations

This evaluation provided good evidence that micro-volunteering works as a way of engaging a willing volunteer force in meeting unmet community need. The micro-volunteering platforms engaged very high numbers of volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The platforms were not necessarily able to capitalise on the willing volunteer force that stepped forward and expressed an interest. There was clearly a very large number of people who saw their willingness convert into no activity at all, and another large group who undertook very little activity. This is potentially a missed opportunity to build volunteer capacity. Low activity was the feature most frequently associated with dissatisfaction amongst volunteers. Despite this, the evidence indicates this group are willing to engage with the micro-volunteering platforms in the future. Action should be taken as a matter of urgency to ensure that this ‘low activity’ group are engaged, and that their disappointing experience does not lead to them being lost to volunteering in the longer term.

The micro-volunteering platforms were good at engaging people who traditionally are less likely to volunteer – particularly those of working age. The combination of platform accessibility (especially the ease of using the app, the simplicity of the tasks and the flexibility of carrying out those tasks around other commitments), and changed personal circumstances during the pandemic (especially having more time because of reduced demands of work and/or restrictions on leisure opportunities) created the conditions for people to take on volunteering work – both those who were already very active volunteers, those who did a bit and those who were not volunteering prior to the pandemic. Volunteering strategies should take advantage of the opportunities for extending the pool of volunteers micro-volunteering offers.

In the conditions of a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, micro-volunteering platforms can act as a catalyst to engage people in additional voluntary work – including those who would not otherwise have volunteered. People learn that volunteering brings rewards – helping others, making a difference, learning new skills, all makes you feel good. They also learn that volunteering can be fitted in around work, family life and leisure. Volunteering strategies need to take account of these findings by communicating messages to the public about the opportunities offered by micro-volunteering that are clear and in a way that engages them.

Outside of the pandemic, effective messaging strategies could include clear articulation of the nature of the ask, such as the problem requiring their assistance, the nature of the commitment from the volunteer, and the rewards volunteering can bring.

Some people may be more motivated by meeting people and making new friends, others may be more interested in learning new skills that might be useful in their employment search. People who work and perceive lack of time as a barrier may be attracted by messages that micro-volunteering can be very quick and easy. Evidence from this evaluation suggests the messages will most effectively be tailored to suit specific segments of the population.

The types of tasks offered by micro-volunteering platforms could usefully be extended – both to reach a wider potential pool of volunteers – engage them and use that as a catalyst to increase their engagement.

There is also evidence that different segments of the population are interested in different types of activities. For example, from the data available more men than women selected roles which focused on driving, so increasing opportunities for these types of activities may better engage them.

The Be My Eyes platform could be regarded as an archetypal micro-volunteering model – an ultimately simple way of connecting volunteers with those who need their support. The approach could offer solutions to other providers as a way of extending reach of their apps to both service users and volunteers, and thus enhancing sustainability.

As demonstrated by the success of Be My Eyes, global infrastructure – both technology and community – can deliver highly effective solutions at the micro-level. Strategies for micro-volunteering could usefully draw on these lessons, including enabling agile solutions that can incorporate technological developments, and build on the possibilities offered by technologies such as 5G.

Interviews with volunteers also highlight that micro-volunteering does not work for all. Therefore, it needs to sit within a comprehensive package of opportunities that encompass a spectrum from archetypal micro-volunteering models such as Be My Eyes to very formal, traditional ways of volunteering, and a range of approaches in between.

The longer-term sustainability of national platforms supporting micro-volunteering could be enhanced by creating local or regional structures, including mechanisms for teamwork and expert and peer support.

NHSVR volunteers suggested expanding the app to capture a wider variety of tasks and allowing tasks for individual clients to be repeated. Feedback suggested that this may be happening informally outside of the app. Allowing this information to be captured and logged could be used to improve the reporting and increase impact of the volunteer programme as a whole.

Microvolunteering report

We’re here to help

Contact us to find out more about our work in Insights and evaluation.