Ready for more?

Move on to the next part in this series:

Progress: how should I adapt an exercise programme based on patient response and other factors?

Click here

As with the exercise tests covered elsewhere in this training, there are a number of absolute and relative contraindications to aerobic or resistance training programmes:

Patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation are likely to have other comorbidities. Two specific comorbidities which may require adjustments to the exercise programme prescribed are:

If a patient has a formal oxygen prescription, they should use their normal prescribed oxygen flow rate while exercising.

Patients using oxygen should be made aware that oxygen saturations should be maintained above 80% while exercising and that if saturation drops below this level, they should stop and seek advice from a medical professional. During exercise classes, clinicians should titrate oxygen to achieve saturations above 90%.

Pulmonary rehabilitation professionals are expected to create personalised exercise programmes for patients with chronic conditions, such as COPD. These programmes should include both aerobic activities (e.g., walking, cycling) and resistance (strength) training. To ensure the programme is safe, suitable, and effective, it should be structured using the FITT-VP principle; this example video guides you through this process.

Exercise prescription can be guided by making sure you consider the FITT-VP principles - Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume and Progression. These principles can be applied to the prescription of both aerobic and resistance exercise.

Alongside these FITT-VP principles, remember to consider the preferences of your patient. Prescribing exercises which the patient enjoys and feels confident performing is likely to improve their engagement with the programme.

The tables below set out guidance based on the FITT-VP principles for prescribing aerobic and resistance training, based on current clinical guidance and best practice. In conjunction with risk assessments and the preferences of the patient, these should form the basis for the exercise programme.

The programme should last at least six weeks, with a minimum of two supervised sessions each week and further sessions performed unsupervised at home.

Aerobic exercise programming may include continuous activity or interval training (sometimes called High Intensity Interval Training; HIIT).

Deciding on which type of aerobic exercise to programme should consider the preferences and capabilities of the patient as well as how the programme is to be delivered. Patients with severe breathlessness may find interval training more acceptable. However, interval training also tends to require closer monitoring from the practitioner.

Before embarking on any exercise programme, it is important to discuss exercising safely with your patient. You should aim to support your patient as they develop their own ability to monitor their levels of exertion, recognising when they are under-exerting themselves (which will limit their progress) and over-exerting themselves (which increases their risk of complications). Instructions on the parameters of safe exercise should be given regularly and reinforced wherever possible (for example, included within exercise programme documents given to the patient).

As a starting point, you should help your patient understand normal physiological responses to exercise:

Patients should be reassured that these responses are to be expected.

In contrast, your patient should also understand the warning signs that they should stop exercising immediately and speak to a medical professional:

Once this baseline understanding has been established, you can start to help your patient understand the different levels of intensity of exercise that may be asked of them during their rehabilitation programme.

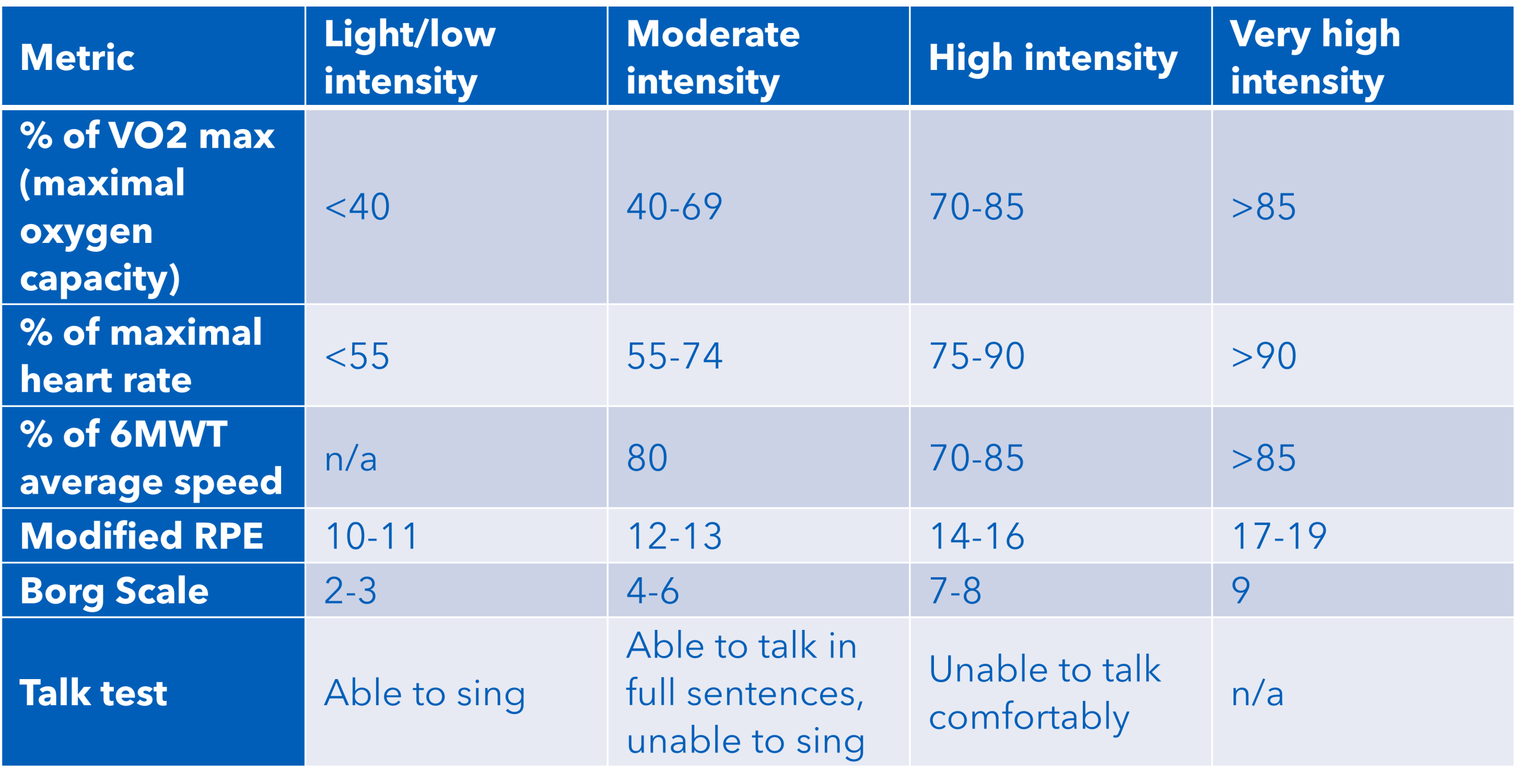

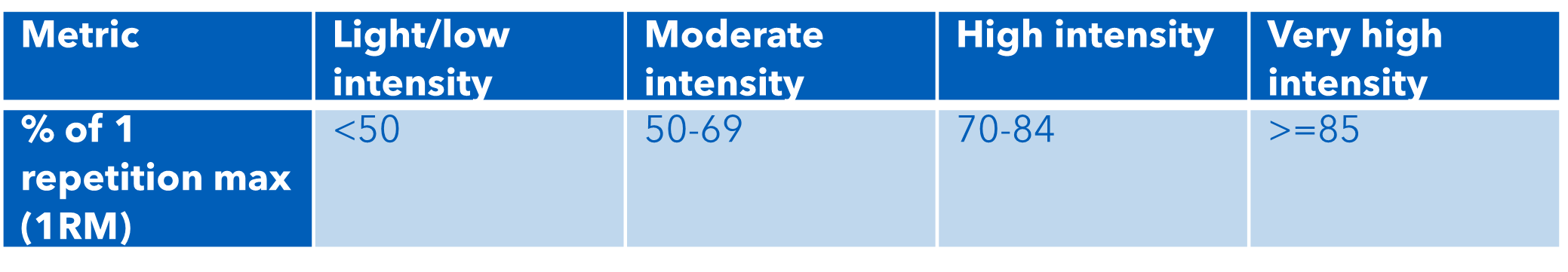

A number of objective and subjective metrics can be used to track exercise intensity depending on context and equipment available. The approximate relationship between these different measures is outlined below, adapted from the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand Guidance:

You should help your patient to understand Borg and Modified RPE scales so that they are able to assess whether their exercise is taking place at an appropriate intensity and make variations where appropriate (e.g. adjusting the pace of aerobic exercise).

You can also teach your patient tactics to help them manage sensations of breathlessness related to exercise:

These tactics and correct pacing will help your patient to avoid stopping during exercise as much as possible.

During supervised exercise sessions, you should monitor heart rate, oxygen saturation and perceived exertion to ensure the exercise session’s intensity remains within safe limits. In particular, any oxygen desaturation below 80% should normally entail stopping the exercise session for that individual.

It is also important to demonstrate the proper use of any weights or other equipment used during exercise sessions.

Whether supervised or completed independently, exercise sessions should always include warmup and cool down phases. Warming up and cooling are important to reduce the risk of injury or exercise-induced complications, as well as helping to optimise performance for the main conditioning phase of the session.

More detailed information about warm-ups and cool downs can be found in the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Cardiovascular Rehabilitation’s Standards for Physical Activity and Exercise in the Cardiovascular Population and on the Asthma and Lung UK website.

Warmups should take about 10-15 minutes for most patients. The exception to this is patients with very low exercise capacity, who are likely to need a shorter warmup phase.

During the warmup phase, your priorities should be:

Good breathing control should be encouraged throughout the warmup to help with the increase in intensity.

A typical warmup before an aerobic session in pulmonary rehabilitation could be structured as below:

This type of warmup would help to mobilise joints, while incrementally increasing the heart rate and preparing the body for exercise.

If using a piece of gym equipment such as a stationary bike for the main portion of the session, you could build in an incremental warmup, working at a lower intensity for a period of time before beginning the main session. As using a single piece of equipment is less likely to fully mobilise the whole body adequately, you should include mobility exercises at the start of the warmup.

If the warmup takes place seated (for example, due to cormorbidities), you should make sure that the patient moves their legs and feet as much as possible to avoid venous blood pooling.

Cool downs are equally important to warm-ups for reducing the risks of exercise-induced complications. The objectives for a cool down are to:

The cool down can be structured in a similar format to a warm up but in reverse – starting with higher-intensity exercise and reducing the intensity as it progresses. Asthma + Lung UK have examples of cool down exercises on their website.

Some healthcare professionals find that setting goals with patients to be a useful motivational exercise, as well as helping with exercise selection for the patient’s programme. Goals may have a beneficial effect on programme adherence if patients can see they are making progress towards or achieving their goals. Conversely, there is also the potential for goals to have a negative impact on motivation if they are not met and the patient feels they are “failing”.

If set, goals could reflect successful progress through the exercise programme (e.g. reaching particular distances for aerobic exercises or weights for resistance training). Goals could also be linked to personal or vocational activities or ambitions, such as:

Goals should be agreed as “SMART” objectives (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely) and revisited as appropriate with the patient. You may wish to use motivational interviewing techniques to help frame goal setting.

Activity diaries may also be helpful for tracking both completion of prescribed exercise programmes and progress against goals set by the patient.

A wide range of personal digital tools, including mobile apps and wearable devices, are focused on supporting physical activity in the general population.

At present, none of these digital tools are routinely recommended for use during pulmonary rehabilitation. Some studies (example) have looked at the use of digital tools during pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD patients. The results of these studies have been inconclusive in terms of benefits and indicate that a significant proportion of pulmonary rehabilitation patients experience difficulties using digital tools.

Some more digitally confident patients may choose to use digital tools for elements of their pulmonary rehabilitation, such as app-based activity diaries or joining online exercise classes.

The pace of change in this area is rapid. For the latest developments, look for recommendations from trusted sources such as the British Thoracic Society or encourage patients to look on the NHS Get Active website.

Move on to the next part in this series:

Progress: how should I adapt an exercise programme based on patient response and other factors?

Click here