Women and birthing people from Black, Asian, or mixed ethnic backgrounds are significantly more likely to experience poor outcomes during their maternity journey.

Between September 2021 and October 2022, Darzi Fellow Rosie Murphy undertook work in Croydon to explore these inequalities and what might be done to improve local services.

This is the second in a series of blogs reflecting on the learnings and experiences from her Fellowship. Read Rosie's first blog focusing on partnering with minoritised women and birthing people and third blog focusing on the challenges of tackling structural issues during fixed-term projects.

Croydon is an ethnically and socially diverse London borough. Approximately 52 per cent of Croydon residents are from minority ethnic backgrounds and this is representative of the maternity population. As such, it felt a particularly appropriate location to spend time understanding why significant perinatal health inequalities related to ethnicity still exist.

Over the course of my time as a Darzi Fellow, I spoke with maternity service-users, staff and other stakeholders from across Croydon about the underlying causes of these health inequalities; you can read about some of methods used to involve people and communities in the project here.

This blog details five recommendations which I hope will support ongoing work in Croydon, but which may also be relevant to other maternity services or health and care services looking to tackle health inequalities.

1. Acknowledge the role of systemic racism in upholding perinatal inequity and make organisational commitments towards becoming anti-racist

This subject was raised during one of the earliest conversations I had with a voluntary sector colleague. At the time, she was also working on a project with a neighbouring mental health trust who had made an organisation-wide commitment to become anti-racist. She felt strongly that this was the minimum standard to build trust and engage with the NHS on projects such as this. During my fellowship there has been a catalogue of publications supporting this recommendation including the Black Maternity Experiences survey, the Birth rights Inquiry into Racial Injustice, the Race and Health Observatory (RHO) report on Ethnic Inequalities in Healthcare and the recent Invisible report from the Muslim Women’s Network.

Of course, it is vital that an organisational commitment to strive towards anti-racism is backed up with a suitable action plan that identifies how this will be achieved - without which, it can serve as a fig leaf to hide inaction.

2. Work collaboratively to find solutions and invest in social capital

Both health and health inequalities are created in the community. The solution to tackling perinatal health inequalities is unlikely to lie within the four walls of a hospital, even if that is where the inequality is being played out. It is therefore crucial that the NHS knows how to work collaboratively with its communities to co-design strategies to tackle perinatal inequalities.

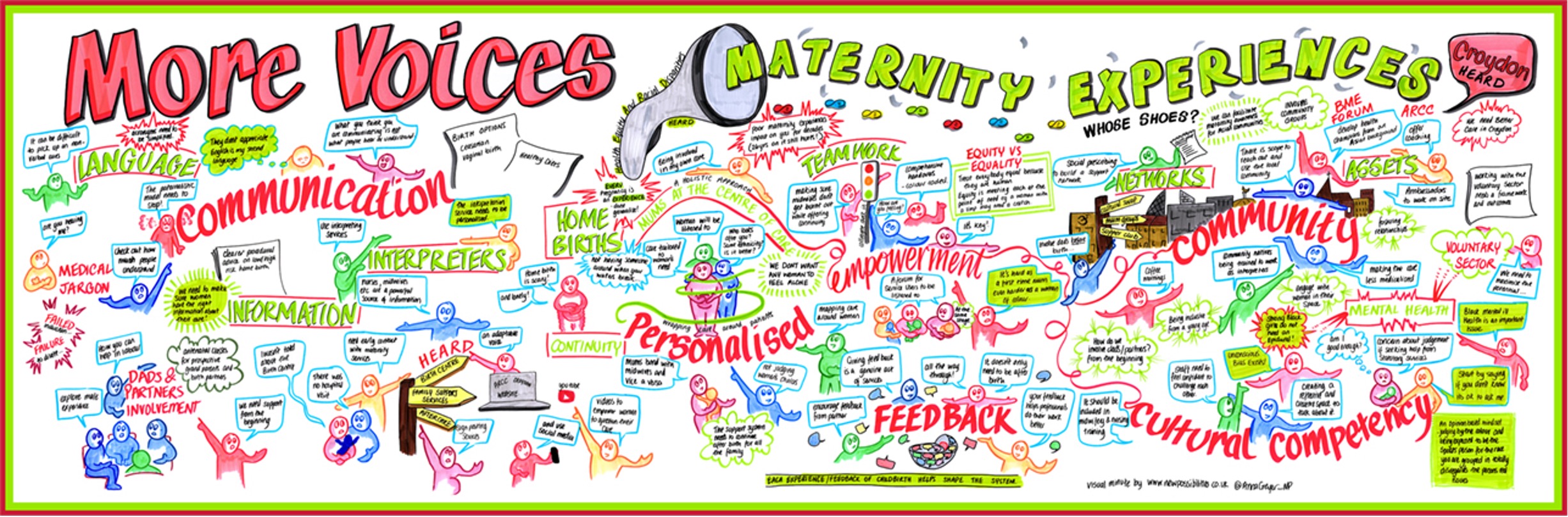

One of the messages that came across strongly from the conversations at the Whose Shoes event was the need for stronger networks to support birthing people and their families; an investment in local “social capital” for pregnancy and early years.

The HEARD campaign is currently working on developing a local maternity programme to meet this need. Ideas included developing maternity peer support, training hairdressers to have conversations about the importance of early referral to maternity services to increase community knowledge levels and a Maternity Champions programme.

3. Invest in effective data capture at a local level

Capturing accurate data around ethnicity in the NHS can be problematic and unreliable. Although there is enough data at a national level to identify the scale of the issue, we don’t consistently have effective data capture at a smaller scale to evaluate of the impact of local initiatives. Without baseline data, assessing the impact of any programmes is difficult because realistic targets cannot be set and funding for projects is jeopardised.

However, some localities have developed effective workarounds. For example, in maternity care, when the childbearing parent is booked in at hospital, a family origin questionnaire is completed to facilitate screening for sickle cell disease or thalassaemia. This could be used to also aid a conversation around the importance of accurate ethnicity data for population health monitoring and as such, upskilling midwives to carry this out could be effective.

Finally, it is important that data capture also considers inequality through an intersectional lens. There is a clear need to improve data capture around other protected characteristics and exclusion health factors in conjunction with ethnicity such as sexuality, religion and deprivation decile or housing insecurity.

4. Listen, hear and take action

The theme of not listening to women has been written large throughout the course of my Darzi Fellowship. Accounts of women not having their concerns listened to, or not taken seriously are an omnipresent feature of sequential maternity reports. When women express choices that go against guidelines or medical advice they are often not supported adequately. Action must be taken to better equip maternity staff to have conversations around informed decision making and personalised care.

Even in circumstances where maternity staff are supportive of women’s bodily autonomy, processes to support fully personalised informed decision-making during labour are not well established. Widespread uptake of new approaches, such as the iDecide tool, are likely to improve the safety, personalisation and experience of labour care.

5. Invest in staff

There remains a widespread misunderstanding about what racism is and how it plays out in health settings, so enabling staff to identify this and supporting them to examine their own bias is so important. Locally delivered cultural awareness training would further support increased safety of personalised maternity care.

A second training recommendation would be to support maternity staff to develop an enhanced understanding and awareness of the role of maternity services in addressing social determinants of health. In maternity services, the perception persists that health interventions such as smoking cessation, weight management and glycaemic control are only required for the duration of the pregnancy. A more long-term view is required to maximise the long term health impact and mitigate against the disparate incidence of chronic disease. Consideration should be given from a commissioning perspective to other opportunities for staff to deliver public health interventions during pregnancy aligned with the prevention agenda. For example, this could be through improving family health and mental health literacy among specific populations.

For any of these recommendations to be implemented, there is also a requirement to invest in a full-time member of staff with a responsibility focused on health inequalities related to ethnicity. Their role would include engaging with the local community and developing the social capital initiatives, embedding cultural shifts, and ensuring that choice and personalisation are protected in maternity care. They would also be there to deliver training as appropriate, set up mechanisms for routine collections of maternity experience feedback and oversee the implementation of new and improved data capture as described earlier in this blog.

With enormous thanks to Ranee Thakar, Gina Short, Olamide Odusanwo, Manjit Roseghini, Donnarie Goldson, Mobola Jaiyesimi, Antoinette Johnson, Leila Howe, Gemma Dakin, Alison White, Jay Patel, Ima Miah, Felisha Dussard, Andrew Brown, Tai Lamard, Gill Phillips, Paul Macey and all the birthing families of Croydon who were so generous in sharing their experiences with me.

Find out more about the maternity and neonatal work happening in South West London ICS.