Innovators working in women’s health often face significant challenges due to a lack of funding across the board. This funding gap is frequently tied to insufficient evidence generation, creating a critical feedback loop where “no data means no funding,” and vice versa. This cycle can slow the development, adoption and scaling of solutions that have the potential to improve women’s health.

In this blog, John Waugh, Finance Support Officer and researcher (MSc in Leadership and Management), explores how innovators with solutions for women's health from the Accelerating FemTech and DigitalHealth.London Accelerator programmes are overcoming this critical feedback loop.

Historically, women’s health has been under-researched, with evidence gaps that persist today. In 1977, for example, a Food and Drug Administration policy recommended that women of childbearing age were excluded from early-phase clinical drug trials in the U.S.

Today, only 7% of healthcare research focuses on conditions that exclusively affect women. Of that research, there is a disproportionate emphasis on reproductive and breast health, often called "bikini medicine", with only 1% of healthcare research and innovation invested in female-specific conditions beyond oncology. This means that other conditions that affect women differently or disproportionately, such as cardiovascular, autoimmune and neurological conditions, remain insufficiently explored.

There has been growing momentum around innovation for women’s health, with the global FemTech market expected to increase year-on-year, reaching an estimated peak market size of over $117 billion in 2029. Despite this predicted growth, just 5% of global healthcare Research and Development (R&D) funding was allocated for women’s health research in 2020.

This lack of foundational evidence and funding for research can discourage investment. This creates a critical feedback loop: the absence of data deters funding, and without funding, innovators cannot gather the evidence needed to validate their solutions, leaving many women without effective care.

However, positive changes are emerging. Innovators within this field are making breakthroughs by diversifying funding sources and seeking specialised programmes that foster collaboration. This blog explores some of these solutions, outlining a blueprint for addressing critical challenges in women's health through properly funded and evidence-informed innovation.

Specialised Accelerators and ringfenced funding for women’s health

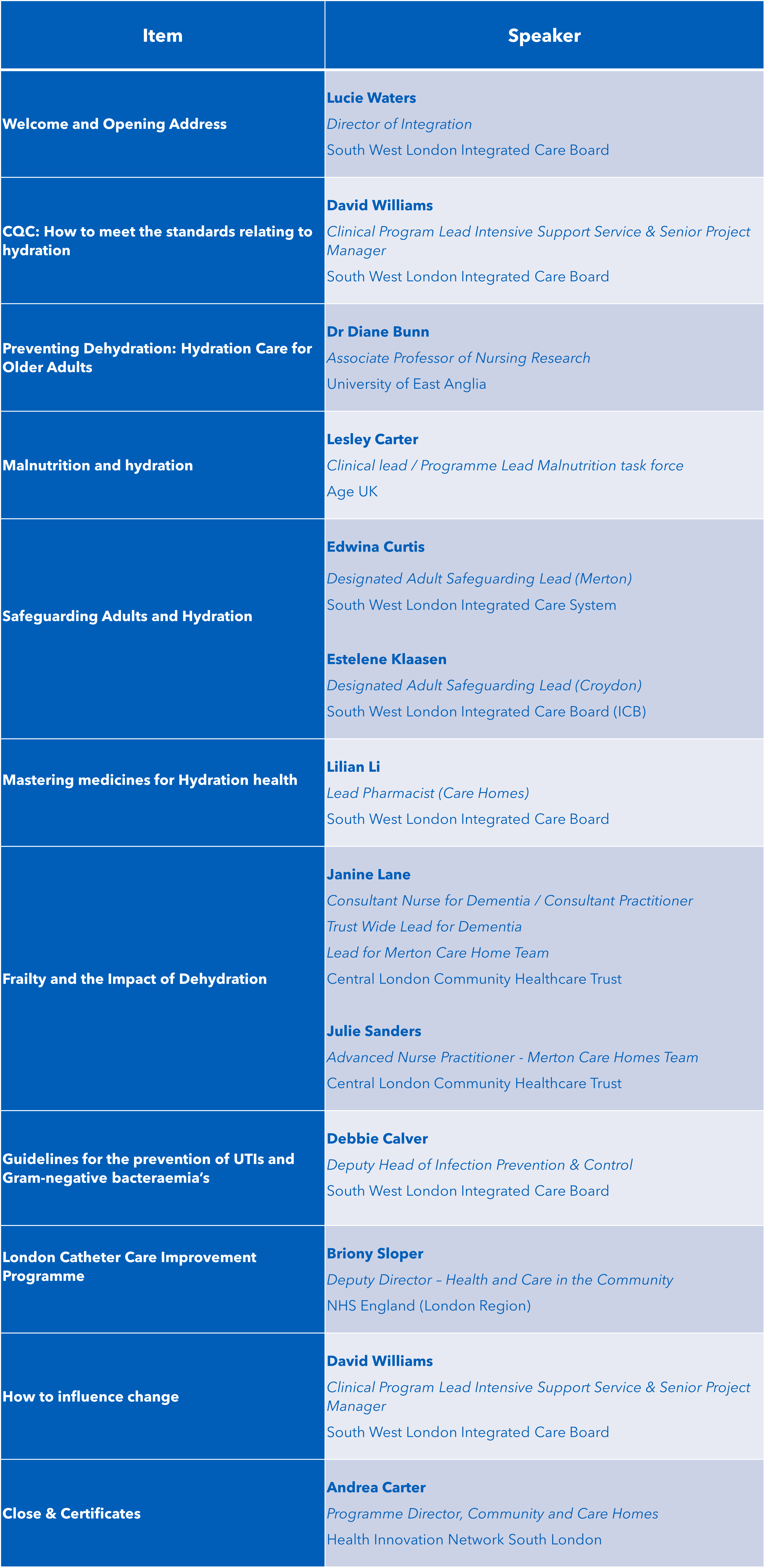

Funding remains the most critical barrier to growth and scaling in women’s health innovation, largely due to a lack of robust data. Programmes such as Accelerating FemTech, The Northern FemTech and Women’s Health Tech Accelerator Programme, Springboard for Female Innovators in Health and SBRI Healthcare are helping to address this by equipping early-stage companies in women’s health with the knowledge, connections and confidence needed to drive initial development stages.

These specialised Accelerators also often provide access to closed call funding pots, supporting innovators to test feasibility and evaluate products. 25 women’s health innovations from across two cohorts of Accelerating FemTech, for example, have secured over £2 million in feasibility funding through special closed call Innovate UK Biomedical Catalyst opportunities accessed through the programme. Elsewhere, Accelerating FemTech alumni Unravel Health, Birthglide and PeriPear have been awarded over £290,000 in SBRI funding.

This combined offer enables innovators in women's health to strengthen their value propositions, progress evaluation and evidence generation, and test commercial viability, whilst also fostering new connections that can drive early investment.

"Obviously, you need to have data, so when you apply for venture capitals and investors, even some grants, they want to see some data. If you don't have money to do some tests to gather data, you can’t get the necessary data.”FemTech company A

Growing awareness of critical challenges in women's health leading

Amongst all G20 nations, the UK has the largest gap in women’s health. It ranks 12th globally, underscoring the impact that lack of awareness, exclusion and underinvestment has had on the advancement of women’s health.

However, a string of recent announcements could signal a meaningful move toward closing the knowledge gap and ensuring women receive the necessary support for their health needs. The renewal of the Women’s Health Strategy, as well as the NHS online hospital’s focus on menopause and menstrual problems which may be a sign of endometriosis, could inform policy and healthcare procurement that supports women's health.

Routine NHS health checks are also set to include advice on menopause for the first time, benefitting almost 5 million women. This marks an important step toward recognising the need for better education on women’s health challenges, such as menopause, which due to long-standing under-research continue to face inadequate support and stigma.

Peppy Health, an alumnus of the DigitalHealth.London Accelerator programme, offers tailored and accessible menopause support. The innovation breaks down barriers and provides expert‑led services by connecting employees with specialised clinicians and trusted resources.

Since taking part in the Accelerator programme, they have since gone on to garner 10x more growth with a Series A investment in 2021 and raise of $45 million in Series B investment in 2023. In 2025, they were selected by the Association of British HealthTech Industries (ABHI) to be part of the eighth cohort of the US accelerator programme, giving Peppy Health the opportunity to expand their business into US markets.

Similarly, Emm, an alumnus of Accelerating FemTech, raised £6.8 million in seed funding. This record round will be used for research and development, as well as supporting the UK launch of their smart menstrual cup, which uses biosensors to provide personal insights from an "overlooked opportunity in women's health:" menstrual blood.

“Female entrepreneurs struggle to get funding from venture capital... they don’t see the inconvenience and the pain that the women go through as a clinical problem.” FemTech company B

Breaking barriers with specialist investors

Bias in the investment landscape remains a major barrier. Venture capitalist (VC) investment team are largely male dominated, with only 13% of senior personnel on UK VC teams being women, and 48% of teams having no women at all. This imbalance limits understanding of women’s health needs and influences funding decisions. Subsequently, leading to women’s health focused innovations being unfunded and women's health needs being unmet.

Specialist healthcare investors are helping to overcome these barriers by leveraging credibility and market expertise to attract additional capital and provide strategic guidance. Their involvement enables innovators in women's health to navigate complex pathways and scale their innovations effectively.

An example of the benefits of specialist investors is evidenced by MyBliss, a company revolutionising sexual wellness, successfully raised through women-led angel groups Mint Ventures, Lifted Ventures and Alma Angels. Networks like these are dedicated to supporting innovators in women's health, enabling companies such as MyBliss to scale its innovation and expand its product range.

“Given that women comprise 50% of the world’s population, it’s hard to fathom that there are still so few intimate female health products that are funded on the market through venture Capitalist firms.” FemTech company C

Overcoming the critical feedback loop

Securing early-stage funding remains a significant challenge for women’s health innovators. Systemic biases in the investment landscape have contributed to a persistent funding gap, which limits the development of data infrastructure, and vice versa.

However, solutions are emerging to address this critical feedback loop. Programmes such as Accelerating FemTech: Evaluate support UK companies developing women’s health solutions by bridging the gap between evaluation (data), funding and innovation. These initiatives help founders build strong value propositions, which can attract future investment.

Elsewhere, more women are entering leadership roles in venture capital and healthcare, increasing representation in decision-making and improving understanding of women’s health needs.

These collaborative efforts signal hope for a more inclusive and innovative future in women’s health, where technology and equity converge to address long-standing gaps in healthcare.

Footnote: Featured quotes were collected during interviews with FemTech companies, as part of a thesis conducted by John Waugh.

Learn more about our work in women's health

Whether you’re a FemTech innovator or you’re working within the health and care system to address health disparities, we can support your mission.

Learn more